How Pharmacy Reimbursement Laws Direct What You Pay for Generic Drugs

You walk into the pharmacy with a prescription for a generic blood pressure pill. The cashier says your copay is $4.50. But last month, it was $12. Why the drop? It’s not because the drug got cheaper. It’s because the rules changed - and those rules are written into federal and state laws that control how pharmacies get paid.

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. But they only account for 23% of total drug spending. That’s the whole point: generics save money. But how much you pay - and how much the pharmacy gets paid - depends on a tangled web of laws, contracts, and reimbursement models. And if you’re on Medicare, Medicaid, or even private insurance, those rules affect you directly.

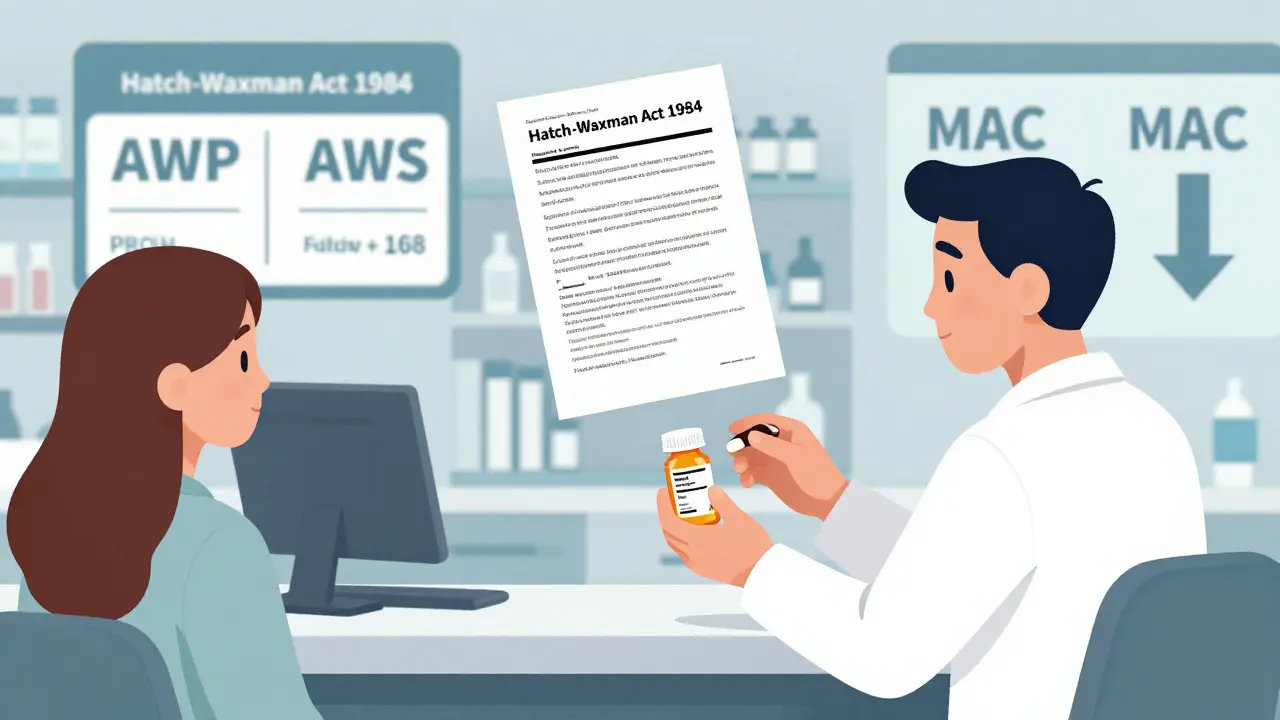

The Foundation: Hatch-Waxman and the Rise of Generics

The modern system for generic drugs started in 1984 with the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before that, companies had to run full clinical trials to prove a generic drug worked - just like brand-name makers. That was expensive and slow. Hatch-Waxman changed that. It let generic manufacturers prove their drug was the same as the brand, without repeating expensive tests. All they had to show was bioequivalence: same active ingredient, same dose, same effect.

This opened the floodgates. Suddenly, dozens of companies could make the same pill. Competition drove prices down. But here’s the catch: the law didn’t fix how pharmacies got paid. That’s where reimbursement models came in - and where the real battles began.

How Pharmacies Get Paid: AWP vs. MAC

When a pharmacy fills a prescription, it doesn’t just get paid for the drug - it gets reimbursed. And there are two main ways that happens for generics: Average Wholesale Price (AWP) and Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC).

AWP used to be the go-to. It’s a list price set by manufacturers, often inflated. Pharmacies would get paid AWP minus, say, 15%. But AWP became a joke. It didn’t reflect what pharmacies actually paid. So states and insurers switched to MAC.

MAC is simpler: it’s the highest amount a plan will pay for a generic drug. If the pharmacy bought the pills for $2 and the MAC is $2.50, they get $2.50. If they paid $3? They eat the loss. That’s why some pharmacies lose money on generics - especially if they’re independent and can’t buy in bulk.

Medicare Part D uses MAC for most generics. So do Medicaid programs. And commercial insurers? Most of them do too. The goal? Pay what the drug actually costs - not what some outdated list says it should.

Medicare Part D: Formularies, Tiers, and the Donut Hole

Medicare Part D covers outpatient prescriptions for seniors. Each plan has a formulary - a list of drugs it covers. Generics usually sit in Tier 1: lowest copay. Brands? Tier 2 or 3. Higher cost.

But here’s the twist: even if a generic is on the formulary, your plan might still require prior authorization. In 2022, 28% of Part D plans made patients jump through hoops just to get a generic. Why? Sometimes it’s to control use. Sometimes it’s because the PBM (pharmacy benefit manager) has a deal with a brand-name maker.

And then there’s the donut hole - the coverage gap. Before 2025, once you spent a certain amount, you paid 100% out of pocket. Now, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act, there’s a $2,000 annual cap. But even with that, if your plan doesn’t cover a generic well, you’re still stuck paying more than you should.

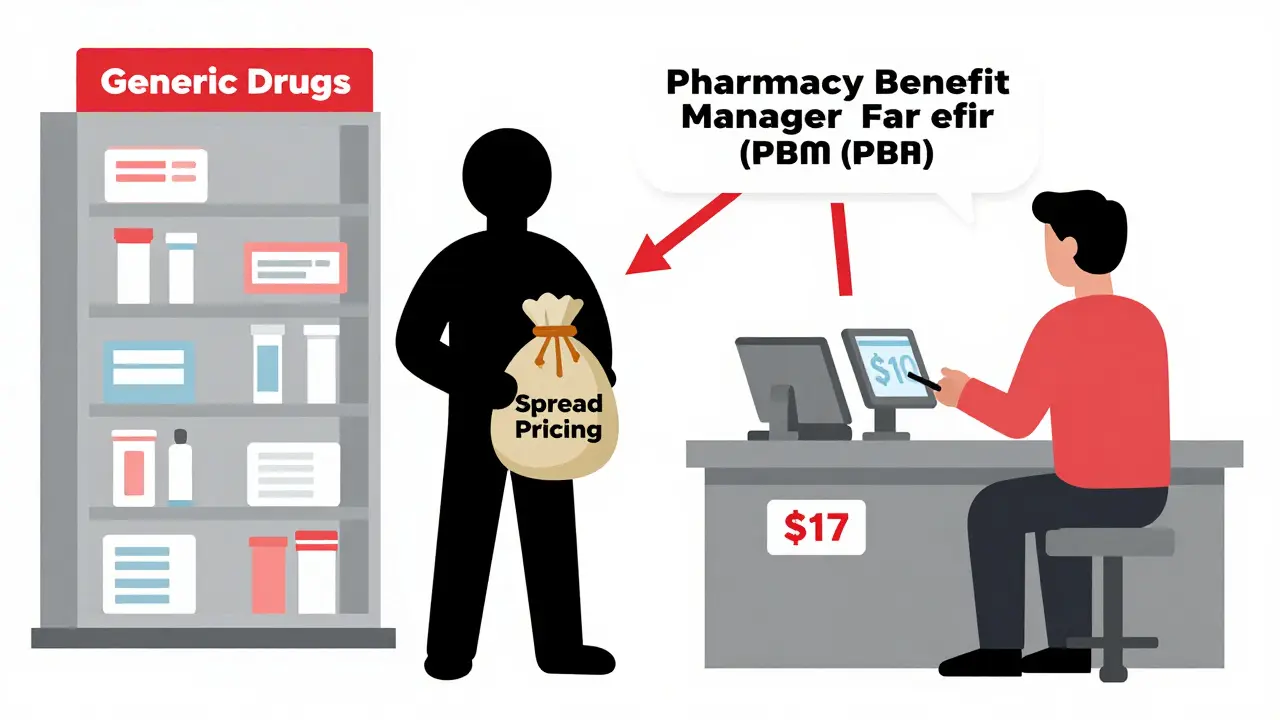

PBMs: The Middlemen Controlling Your Costs

Who’s behind the scenes pulling strings? Pharmacy Benefit Managers - PBMs. CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRX. These three control over 80% of all prescription claims in the U.S.

They don’t sell drugs. They don’t run pharmacies. But they negotiate prices with manufacturers, set reimbursement rates for pharmacies, and decide which drugs go on formularies. Their profit? Comes from two places: rebates from drug makers and spread pricing.

Spread pricing is the sneaky part. The PBM tells your insurer, “We’ll pay $10 for this generic.” But they only pay the pharmacy $7. The $3 difference? That’s their profit. And you never see it. Until you find out your cash price is $5 - cheaper than your insurance copay.

That’s why gag clauses were banned in 2018. Pharmacists used to be forbidden from telling you that paying cash might save you money. Now they can. But many still don’t - because they’re afraid of losing network access.

State Laws Are Changing the Game

As federal rules get more complex, states are stepping in. Forty-four states now have laws regulating how PBMs reimburse pharmacies for generics. Some ban spread pricing. Others require PBMs to pay pharmacies based on actual acquisition cost.

In 2023, Minnesota passed a law requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing models. Texas now caps how much PBMs can charge pharmacies for dispensing fees. These aren’t just bureaucratic tweaks - they’re direct attempts to protect small pharmacies and lower patient costs.

Medicaid programs also use Preferred Drug Lists (PDLs). If a generic isn’t on the list, you might need prior authorization - or pay more. States update these lists annually. And guess who picks them? A Pharmacy and Therapeutics Committee - usually made up of doctors, pharmacists, and insurers.

The $2 Drug List: A New Model for Medicare

In 2025, CMS is testing something new: the Medicare $2 Drug List. It’s simple. For about 100-150 generic drugs - ones that are clinically important, widely used, and already cheap - Medicare Part D plans will charge a flat $2 copay.

No tiers. No formulary restrictions. No prior auth. Just $2. That’s it.

This model is inspired by Walmart and Kroger, who’ve been selling common generics for $4 or less for years. Now Medicare wants to bring that to seniors. If it works, it could become permanent. And if it does, it could force PBMs to stop hiding behind complicated pricing.

Why Pharmacists Are Struggling

Independent pharmacies are getting crushed. In 2018, the average profit margin on a generic prescription was 3.2%. By 2023? It dropped to 1.4%. Some are operating at a loss.

Why? MAC rates haven’t kept up with wholesale prices. PBMs cut dispensing fees. And the cost of running a pharmacy - rent, staff, compliance - keeps rising. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs still bring in higher margins. So some pharmacies focus on those - even though they’re not the most cost-effective option for patients.

And don’t forget the paperwork. One study found that pharmacy staff spend 19.3 hours a week just handling prior authorizations. That’s almost half a workday. All to get a $2 generic approved.

What This Means for You

Here’s what you need to know:

- If you’re on Medicare, ask if your generic is on the $2 list - even if it’s not on your plan’s formulary.

- Always ask the pharmacist: “What’s the cash price?” It’s often cheaper than your copay.

- Check your plan’s formulary. If a generic is in Tier 3, it might be cheaper to pay out of pocket.

- Don’t assume your insurance is saving you money. Sometimes, it’s the opposite.

Generics are supposed to be the solution. But the system designed to help them is full of loopholes, hidden fees, and perverse incentives. Laws meant to lower costs often end up protecting middlemen - not patients.

The real test isn’t whether generics work. It’s whether the system will finally pay pharmacies fairly - so they can keep giving you the drugs you need at a price you can afford.

What’s Next? The Future of Generic Reimbursement

The FTC is cracking down on “pay-for-delay” deals - where brand-name companies pay generic makers to delay entry. That’s good. More competition means lower prices.

ICER predicts generic prices will keep falling 5-7% a year through 2027. But if reimbursement models don’t change, pharmacies won’t survive to fill those prescriptions.

Value-based payment models are coming - where pharmacies get paid based on outcomes, not volume. But that’s years away. In the meantime, the $2 Drug List might be the most meaningful reform in a decade.

If it works, it won’t just save money. It’ll restore trust. Patients will know they’re getting the best deal. Pharmacies will know they’re being paid fairly. And the system - finally - will work for the people it’s supposed to serve.

Why is my generic drug copay higher than the cash price?

Your insurance plan may be using spread pricing - where the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) charges your insurer more than what they pay the pharmacy. The difference becomes profit for the PBM. Meanwhile, the cash price reflects the actual wholesale cost. Always ask your pharmacist for the cash price - it’s often cheaper than your copay, especially for common generics.

What is MAC pricing and how does it affect me?

MAC stands for Maximum Allowable Cost. It’s the highest amount your plan will reimburse the pharmacy for a generic drug. If the pharmacy pays more than the MAC to buy the drug, they lose money on that prescription. That’s why some pharmacies won’t fill certain generics - they can’t afford to. It doesn’t change your copay directly, but it limits which generics are available at your pharmacy.

Are all generic drugs covered the same way by Medicare?

No. Medicare Part D uses formularies with tiers. Most generics are in Tier 1 with the lowest copay. But some plans put certain generics in higher tiers if they’re newer, have limited competition, or are part of a brand’s “authorized generic” strategy. Always check your plan’s formulary and ask if a generic is preferred.

Why do some pharmacies refuse to fill my generic prescription?

It’s usually because the reimbursement rate (like MAC) is lower than what the pharmacy paid to buy the drug. Independent pharmacies often operate on razor-thin margins. If they’re forced to sell a generic at a loss, they may refuse it - especially if the drug is low-demand or has frequent supply issues. This is more common with small, local pharmacies than big chains.

What is the Medicare $2 Drug List and how does it help?

The Medicare $2 Drug List is a new voluntary model starting in 2025. It sets a flat $2 copay for about 100-150 clinically important generic drugs - regardless of your plan. This removes formulary restrictions and tiered pricing. It’s designed to improve adherence and lower out-of-pocket costs. If you take one of these drugs, your copay will be $2 - no matter which Part D plan you’re on.

Can I get my generic drug cheaper without insurance?

Yes. Many large retailers like Walmart, Costco, and Kroger sell common generics for $4-$10 per month - often cheaper than insurance copays. You don’t need insurance to use these programs. Ask your pharmacist to compare your insurance copay with the cash price before you pay.

What You Can Do Today

Don’t wait for the system to fix itself. Take control:

- Always ask for the cash price - even if you have insurance.

- Check your plan’s formulary online. Look for “preferred” generics.

- Use retail pharmacy discount programs for common drugs like metformin, lisinopril, or atorvastatin.

- If your pharmacy refuses a generic, ask why. It might be a reimbursement issue - not a medical one.

- Advocate. Contact your state representative if you’re seeing frequent issues with generic access.

The goal of generic drugs is simple: save money without sacrificing care. But the system has gotten complicated. Laws matter. Reimbursement models matter. And your choices - asking questions, comparing prices, speaking up - matter too.

david jackson

December 26, 2025 AT 21:23Let me tell you, this whole system is a circus. I mean, you’ve got these PBMs acting like middlemen mafia bosses, siphoning off dollars while pharmacies bleed out trying to stay open. And the worst part? You, the patient, are stuck in the middle, confused as hell because your $4.50 copay last month turned into $12, then back to $4.50, and no one can explain why. It’s not about the drug-it’s about who gets paid what, and who’s hiding the receipts. The MAC system sounds fair on paper, but in practice? It’s a death sentence for small pharmacies. I’ve seen my local pharmacy refuse to fill a $2 generic because the reimbursement was $1.80. They’re not being greedy-they’re just trying not to go under. And don’t even get me started on the donut hole. It’s not a hole-it’s a black hole that swallows your dignity and your savings. The $2 Drug List? Finally, someone’s thinking like a human being, not a spreadsheet. If this works, it could be the first real win for patients in decades. But I’m not holding my breath. The system doesn’t change unless it’s forced to-and right now, the only ones forcing it are the ones who can’t afford to pay anymore.

Jody Kennedy

December 27, 2025 AT 23:58YESSSSSS this is SO IMPORTANT!! 🙌 I just found out my metformin is cheaper at Walmart than my copay-like, $4 vs $12?? I almost cried. Why do we let corporations make us feel guilty for asking for a fair price? You don’t need insurance to get affordable meds. You just need to know the system’s rigged-and then outsmart it. Tell your pharmacist. Tell your mom. Tell your neighbor. This isn’t just about money-it’s about dignity. We deserve to be healthy without going broke. #AskForCashPrice #GenericsAreNotCheapTheyreJustHidden

wendy parrales fong

December 29, 2025 AT 12:01It’s weird, right? We all want generics to work. They’re safe, effective, and way cheaper. But the system that’s supposed to make them accessible is actually making them harder to get. It’s like building a highway to save time, but then putting toll booths every mile and charging extra for the signposts. The real problem isn’t the drugs-it’s the people who profit from confusion. PBMs aren’t evil-they’re just following a model designed to maximize profit, not care. Maybe the answer isn’t more laws, but simpler ones. Like: pay the pharmacy what they paid for the drug, plus a fair fee. No spreads. No rebates. No games. Just honesty. And if that means PBMs make less money? Maybe that’s okay. Patients are paying enough already.

Jeanette Jeffrey

December 29, 2025 AT 16:27Oh wow. Another ‘poor patient’ sob story. Let me guess-you think pharmacies are saints and PBMs are demons? Newsflash: pharmacies make money on brand-name drugs and push them harder because they’re more profitable. And you’re mad about $4.50? Try living in a country where you pay $200 for insulin and no one bats an eye. You want change? Stop blaming middlemen and start blaming the doctors who write 90% of these prescriptions without checking prices. And don’t even get me started on how you all act like cash prices are some magical secret. They’ve been public for years. You just don’t want to do the work. Grow up.

Shreyash Gupta

December 30, 2025 AT 01:35bro this is so real 😭 i live in india and here generics are $0.10 and pharmacies give you 3 months supply for $1.50. here in us? you get charged $12 for the same pill. how? why? who? 🤡 why do we let this happen? i just want to cry. also i paid cash for my lisinopril at cvs and it was $3. my copay was $11. i feel like i was scammed by my own insurance. 😔

Ellie Stretshberry

December 31, 2025 AT 02:03i never knew about the cash price thing until last month when my grandma asked the pharmacist and it saved her $80 a month. i feel dumb for not asking sooner. also i think the $2 list is a good idea but i hope they dont forget the little guys who run pharmacies in towns no one cares about. they need help too. just saying. 🤗

Zina Constantin

December 31, 2025 AT 09:53As someone who works in global health policy, I can tell you this: the U.S. is an outlier. In nearly every other developed country, generic drug pricing is transparent, regulated, and tied directly to manufacturing cost. The fact that we’ve allowed a corporate labyrinth to control access to life-saving medication is not just inefficient-it’s unethical. The $2 Drug List is a step in the right direction, but it’s a Band-Aid on a broken leg. What we need is a national price ceiling for generics, enforced by the federal government, with penalties for spread pricing. No more hiding. No more games. Just fair access. And if PBMs can’t adapt? Then they shouldn’t be in this business.

Dan Alatepe

December 31, 2025 AT 22:36man… i just wanna say… this system is a full-on nightmare 😭 the way they treat pharmacies like trash? and patients? like we’re just numbers? i seen my cousin’s pharmacy shut down last year because they couldn’t afford to fill a $2 pill. they had to lay off 3 people. that’s not capitalism. that’s cruelty. and the worst part? no one cares until it’s their mom’s blood pressure med. wake up america. this ain’t about politics. this is about people. 💔

Angela Spagnolo

January 1, 2026 AT 11:54...i just... i didn’t realize... i mean, i knew prices were weird, but i didn’t know PBMs were making money off the difference... like, the actual difference... between what they charge and what they pay... and that’s why my copay is higher than cash... and i feel... so... confused... and kinda sad... and also... i’m gonna start asking for cash prices now... but i’m scared to... what if they say no... or... i don’t know... what if i’m wrong...?

Sarah Holmes

January 2, 2026 AT 05:13How is it even possible that a nation with the highest per-capita healthcare spending in the world cannot deliver a basic, generic, off-patent medication at a cost that reflects its actual manufacturing price? This is not a market failure-it is a moral collapse. The fact that pharmacy benefit managers, entities with zero clinical expertise, are allowed to dictate reimbursement rates to healthcare providers while pocketing the difference is not just scandalous-it is criminal. And you, the reader, are complicit if you continue to accept this as normal. The $2 Drug List is a PR stunt. Real reform requires dismantling PBMs entirely. And if you think that’s radical, ask yourself: why are we allowing corporations to profit from our suffering?

Jay Ara

January 2, 2026 AT 15:34bro just ask the pharmacist for cash price every time. it’s that simple. no drama. no politics. just do it. my dad’s atorvastatin is $4 at walmart. my insurance wanted $15. i paid cash. done. no one’s gonna fix this for you. you gotta fix it for yourself. peace

Michael Bond

January 3, 2026 AT 03:43Ask for cash price. Always.

SHAKTI BHARDWAJ

January 3, 2026 AT 10:02Ohhh so now the system is ‘rigged’? Newsflash: the government created this mess with Hatch-Waxman and then handed the keys to PBMs. You want change? Stop blaming the middlemen and start blaming the politicians who wrote the laws. And don’t give me that ‘$2 drug list’ fairy tale. It’s just another layer of control. They’ll make you dependent on it. Then they’ll raise it to $3. Then $5. Then they’ll say ‘we tried’. Meanwhile, the real solution? Let pharmacies negotiate directly with manufacturers. No PBMs. No formularies. Just free market. But no, you’d rather whine on Reddit than actually demand real competition.

Matthew Ingersoll

January 4, 2026 AT 08:32I’ve worked in pharmacies for 18 years. I’ve seen this play out. The MAC system is broken. The $2 list? It’s a start. But the real issue? We’re not paid for care-we’re paid for volume. And when you’re paid $1.50 to dispense a pill that cost you $2.10, you stop filling it. That’s not greed. That’s survival. The only way this changes is if we start paying pharmacists for counseling, adherence support, medication reviews-not just for handing out pills. We’re healthcare providers, not cashiers. And we deserve to be treated like it.

carissa projo

January 5, 2026 AT 16:45There’s something beautiful about how a $2 pill can carry so much weight. It’s not just medicine-it’s dignity. It’s the difference between taking your blood pressure drug every day and skipping it because you’re choosing between groceries and your heart. This isn’t about politics or profit. It’s about the quiet moments: an elderly woman nodding at the pharmacist because she knows she can afford her meds today. A father breathing easier because his kid’s asthma inhaler doesn’t cost a week’s paycheck. The system was built to save money. But money isn’t the point. People are. And if we can make a $2 drug accessible to every senior in America, maybe we’re finally learning how to care for each other. Not as customers. Not as numbers. But as humans.