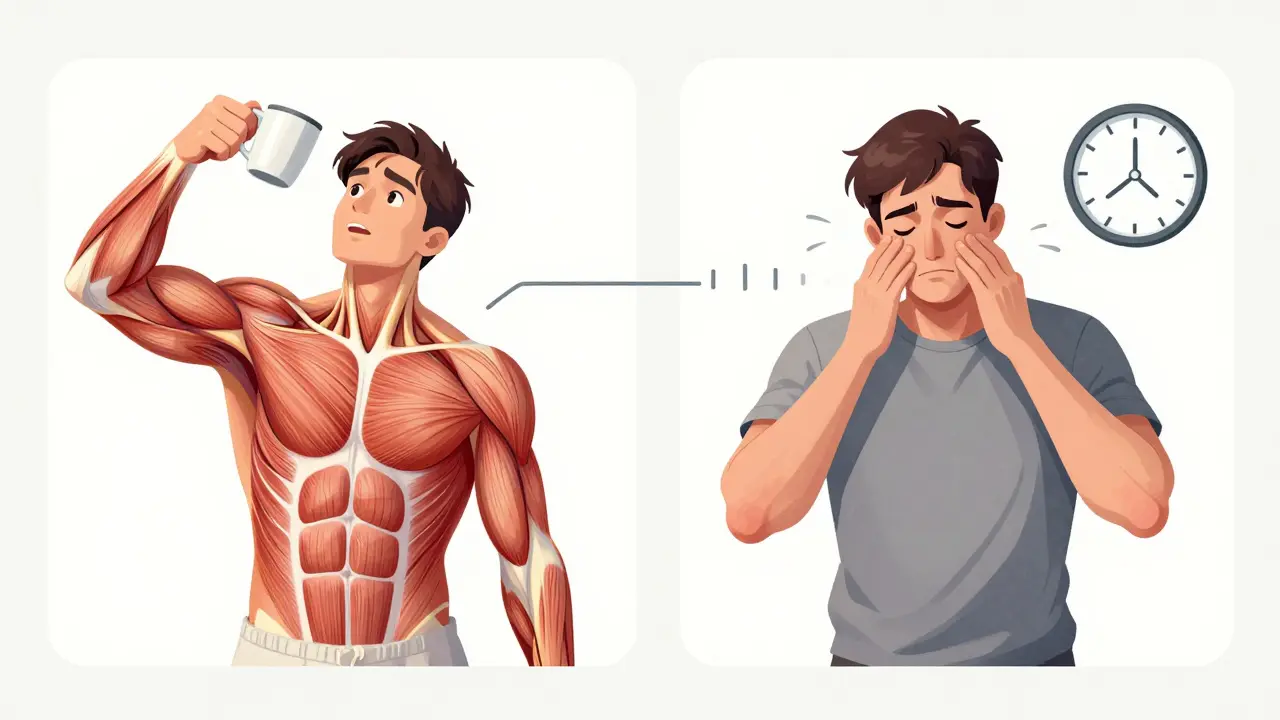

Myasthenia gravis isn’t just muscle weakness. It’s weakness that gets worse when you use your muscles-and gets better when you rest. Imagine trying to hold up your eyelids, only to have them droop after reading a few lines. Or swallowing a bite of food, only to choke because your throat muscles suddenly give out. Then, after a nap, everything feels normal again. That’s the hallmark of myasthenia gravis: fatigable weakness.

What Exactly Is Fatigable Weakness?

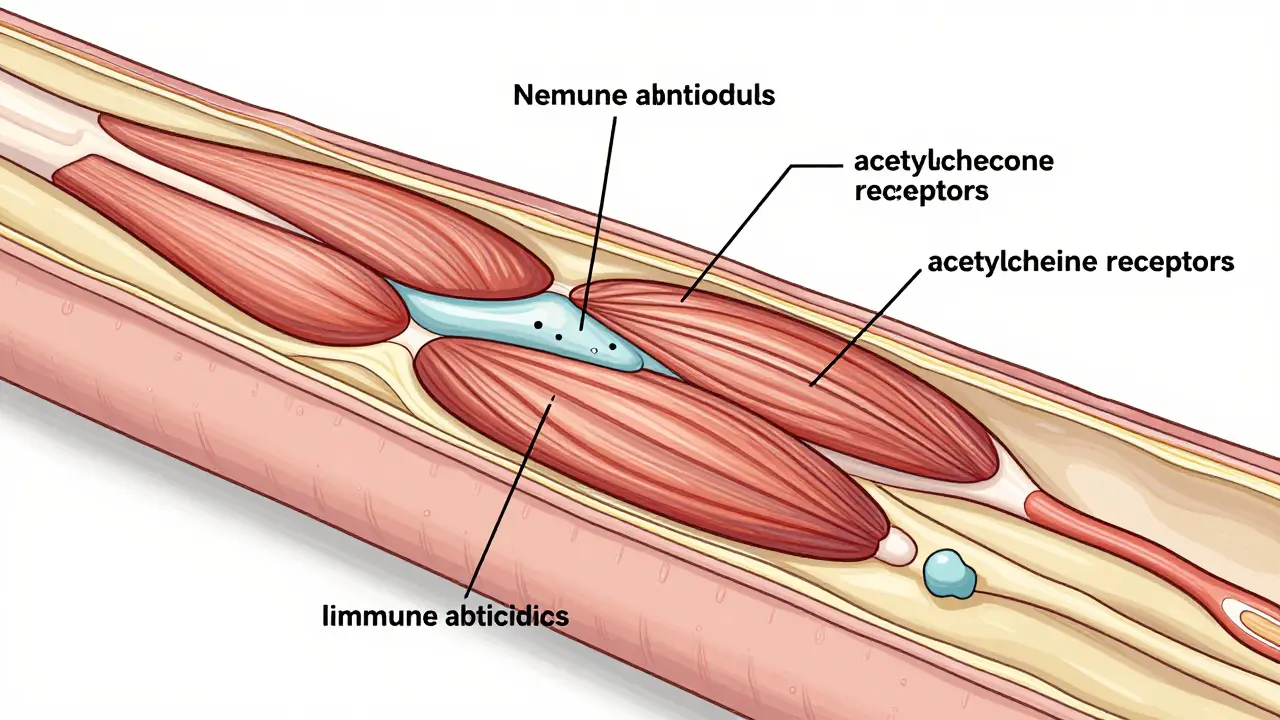

Most muscle fatigue comes from overuse-like your legs burning after a long run. But in myasthenia gravis, the problem isn’t your muscles. It’s the connection between your nerves and muscles. Your body’s immune system mistakenly attacks the receptors on muscle cells that receive signals from nerves. These receptors normally respond to a chemical called acetylcholine. When they’re blocked or destroyed, the signal doesn’t get through. The muscle can’t contract properly.

This isn’t constant weakness. It’s fatigable weakness. The more you use the muscle, the weaker it gets. Eyes tire first-85% of people with MG start with drooping eyelids or double vision. Then come the bulbar muscles: trouble speaking clearly, chewing, or swallowing. Limbs follow-arms feel heavy lifting a coffee cup, legs buckle climbing stairs. Rest brings relief. That’s why people with MG often nap after meals or avoid long walks.

Who Gets Myasthenia Gravis?

MG doesn’t pick favorites, but it does have patterns. About two-thirds of cases begin before age 50, often in women. These early-onset cases are usually tied to thymus gland issues-like thymic hyperplasia, where the gland is enlarged but not cancerous. The other third starts after 50, more often in men. In this group, about 1 in 7 have a thymoma-a tumor in the thymus. It’s not always cancerous, but it’s linked to more severe MG.

Not everyone has the same antibodies. Around 80-90% have antibodies against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). About 5-8% have antibodies against MuSK, a different protein at the neuromuscular junction. The rest are seronegative-no known antibodies detected, but the symptoms still fit. Each subtype responds differently to treatment. That’s why testing matters.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Doctors don’t just guess. They test. A simple bedside test? Ask the patient to stare upward without blinking. If their eyelids droop after 30 seconds, that’s a red flag. Blood tests check for AChR or MuSK antibodies. If those are negative but suspicion remains, an electromyography (EMG) can show the signal breakdown between nerve and muscle. The repetitive nerve stimulation test reveals a drop in muscle response after repeated signals-a classic sign of MG.

The Quantitative Myasthenia Gravis Score (QMGS) helps track severity. A score above 11 means moderate to severe disease. That’s when doctors move beyond just easing symptoms and start targeting the immune system.

First-Line Treatments: Symptom Relief

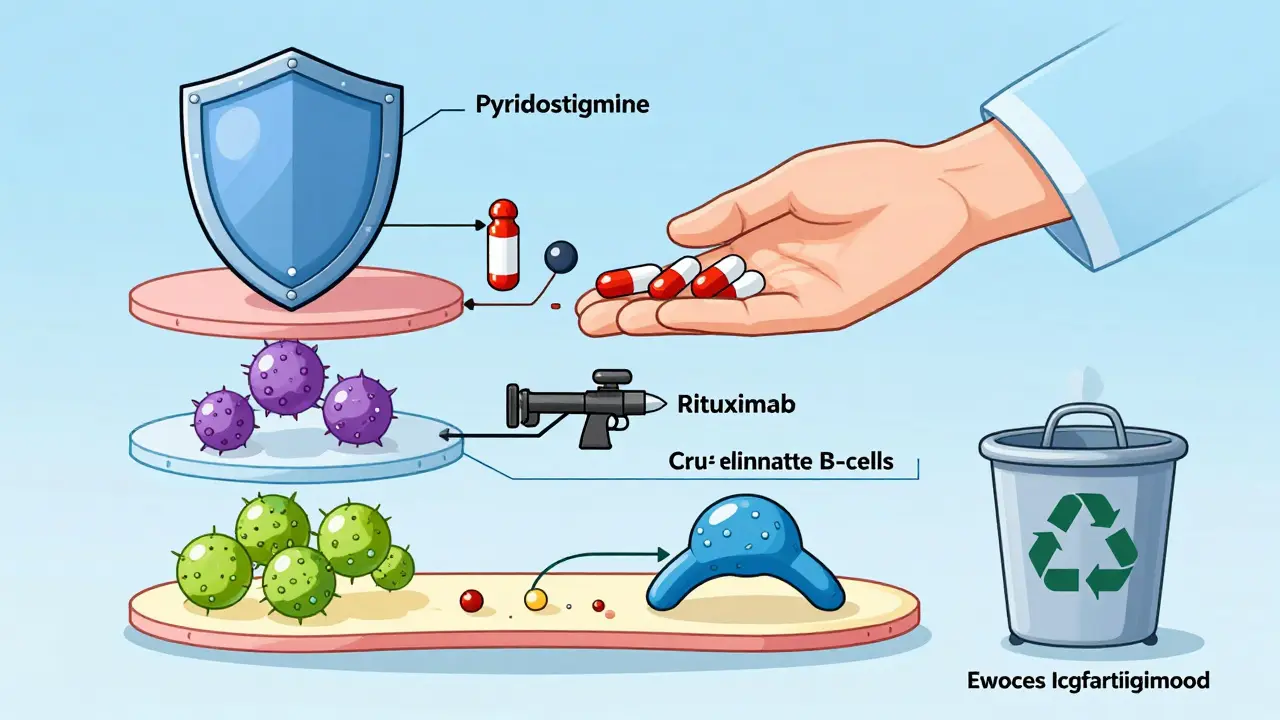

Pyridostigmine is the go-to starter drug. It’s an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor-it stops the body from breaking down acetylcholine too fast, so more of it hangs around to help nerves talk to muscles. Doses range from 60 to 240 mg daily, split into 3-4 doses. It helps with drooping eyes, weak speech, and chewing. But it doesn’t fix the root problem. It just buys time.

Side effects? Cramps, nausea, diarrhea, excessive salivation. It’s not a cure. It’s a bridge-until stronger treatments kick in.

Immunotherapy: Turning Off the Attack

Once symptoms go beyond mild, immunotherapy becomes essential. Corticosteroids like prednisone are the most common first-line immunosuppressant. Starting at 0.5-1.0 mg per kg of body weight, they suppress the immune system enough to let the neuromuscular junction heal. About 70-80% of patients see major improvement or even full remission. But here’s the catch: long-term use brings weight gain, diabetes, bone loss, and mood swings. Seven out of ten patients on daily prednisone over 10 mg gain noticeable weight.

That’s why steroid-sparing agents are added within 1-2 months. Azathioprine (2-3 mg/kg/day) and mycophenolate mofetil (1000-1500 mg twice daily) take months to work but let doctors reduce steroids over time. Azathioprine works in 60-70% of patients after 12-18 months. Mycophenolate hits 50-60%. But both carry risks-liver damage in 15-20% with azathioprine, increased infection risk overall.

Special Cases: MuSK and Seronegative MG

MuSK-positive MG doesn’t respond well to standard drugs. Azathioprine? Less effective. Steroids? Often needed long-term. But rituximab-a drug that wipes out B-cells-works wonders here. Studies show 71-89% of MuSK-positive patients reach minimal symptom status after rituximab, compared to only 40-50% in AChR-positive cases. It’s now a first-line option for MuSK patients, not just a last resort.

Seronegative MG is trickier. No clear antibody means no targeted test. But if symptoms match and EMG confirms, treatment follows the same path: pyridostigmine, then steroids, then immunosuppressants. Some respond to rituximab anyway, even without known antibodies.

Fast-Acting Rescue: IVIG and Plasma Exchange

When someone with MG suddenly can’t swallow, breathe, or stand up-that’s a myasthenic crisis. It’s an emergency. You need fast results. That’s where IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin) and plasma exchange (PLEX) come in.

IVIG floods the body with healthy antibodies that confuse the immune system, making it stop attacking. Effects show in 5-7 days and last 3-6 weeks. It’s safe, no needles in big veins, but expensive and requires multiple IVs over days.

PLEX literally pulls blood, removes the bad antibodies, and returns clean blood. It works faster-2-3 days-and is preferred in severe bulbar or breathing problems. But it needs a central line, carries infection and clotting risks, and isn’t available everywhere.

Experts agree: both are equally effective. Choose based on access, urgency, and patient health.

Thymectomy: Removing the Trigger

For early-onset AChR-positive MG between 18 and 65, removing the thymus isn’t optional-it’s recommended. The MGTX trial showed patients who had thymectomy reached symptom-free status 1.88 times faster than those on drugs alone. After five years, 35-45% of these patients go into complete remission-no drugs needed.

Even if the thymus looks normal, it’s still acting as an immune training ground for the wrong cells. Surgery helps reset the system. Minimally invasive techniques now mean shorter recovery and less pain.

New Frontiers: nFcR Antagonists

For years, MG treatment was stuck between steroids and broad immunosuppressants. Now, a new class of drugs is changing the game: neonatal Fc receptor (nFcR) antagonists. Efgartigimod, approved in 2021, binds to the receptor that normally recycles IgG antibodies. It blocks that recycling-so the body breaks down the bad antibodies faster. In the ADAPT trial, 68% of patients reached minimal manifestation status within weeks. IgG levels dropped 60-75% in seven days.

It’s given as a weekly IV infusion for four weeks, then as needed. No need for hospitalization like PLEX. Fewer side effects than steroids. It’s not a cure, but it’s a powerful tool for people who don’t respond to other treatments-or who can’t tolerate long-term immunosuppression.

Ravulizumab, approved in 2023, blocks the complement system, another part of the immune attack. It’s the first complement inhibitor for MG. Both drugs represent a shift from broad immune suppression to precise antibody targeting.

What About Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors?

Here’s a dangerous twist: cancer drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) can trigger MG-or make it worse. In a 2022 case series, 60% of patients who developed MG after ICI treatment also had heart inflammation (myocarditis). Eighty-three percent needed ICU care. If you have MG and get cancer, your oncologist must know. These drugs can turn mild MG into a life-threatening emergency.

Long-Term Management: The Real Challenge

Most people with MG need long-term treatment. Eighty-five to ninety percent stay on some form of immunosuppression. But the goal isn’t just control-it’s remission. Experts say you shouldn’t try to taper meds until you’ve been in minimal manifestation status for at least two years. Taper too soon? Forty to fifty percent relapse.

Younger patients, especially after thymectomy, have the best shot at stopping all meds. But for many, it’s a balancing act: enough treatment to stay strong, not so much that you’re constantly sick from side effects.

What’s Next?

As of 2023, over 15 clinical trials are testing new therapies: drugs that target specific B-cells, block cytokines, or silence immune signals. The goal? Disease modification without lifelong immunosuppression. One day, MG might be managed like diabetes-with daily pills or monthly shots that keep the immune system in check, not shut down.

For now, the message is clear: MG is treatable. Fatigable weakness isn’t your fault. It’s not in your head. And with the right combination of drugs, surgery, and monitoring, most people can live full, active lives.

Is myasthenia gravis curable?

There’s no universal cure, but many people achieve long-term remission. About 35-45% of early-onset AChR-positive patients who have a thymectomy go into complete remission within five years and no longer need medication. Others manage symptoms effectively with immunotherapy and live without major limitations.

Can stress make myasthenia gravis worse?

Yes. Stress, infections, and extreme heat can trigger flare-ups by activating the immune system. Managing stress through sleep, pacing activities, and avoiding overheating is part of daily care. Many patients keep a symptom diary to spot triggers.

Does myasthenia gravis affect life expectancy?

With modern treatment, most people with MG have a normal lifespan. The biggest risk is myasthenic crisis-when breathing muscles fail. That’s rare now with early intervention. Deaths are usually linked to complications from infections or delayed treatment, not the disease itself.

Can I get pregnant with myasthenia gravis?

Yes, but it requires careful planning. MG symptoms can worsen during pregnancy, especially in the first trimester and postpartum. Some medications like azathioprine and prednisone are considered safe during pregnancy. Always work with a neurologist and obstetrician experienced in autoimmune conditions.

Why do some people with MG need IVIG while others don’t?

IVIG is used for acute worsening or crisis-not routine maintenance. If symptoms are stable on oral meds, IVIG isn’t needed. It’s reserved for when weakness suddenly gets severe, like trouble swallowing or breathing. It’s a bridge to longer-term immunosuppression, not a lifelong solution.

Are there natural remedies for myasthenia gravis?

No proven natural remedies exist. Supplements like vitamin D or omega-3s may support general health but don’t affect the autoimmune process. Avoid unregulated herbal products-they can interfere with medications or trigger immune reactions. Stick to evidence-based treatments.

Jasneet Minhas

January 30, 2026 AT 07:33Eli In

January 31, 2026 AT 02:01Paul Adler

January 31, 2026 AT 22:23Robin Keith

February 2, 2026 AT 10:38Sheryl Dhlamini

February 3, 2026 AT 23:27Doug Gray

February 5, 2026 AT 09:21Kristie Horst

February 6, 2026 AT 05:42LOUIS YOUANES

February 6, 2026 AT 17:44Andy Steenberge

February 8, 2026 AT 16:10Laia Freeman

February 10, 2026 AT 10:13Pawan Kumar

February 11, 2026 AT 11:27rajaneesh s rajan

February 13, 2026 AT 06:46