Dopamine Interaction Calculator

Risk Assessment

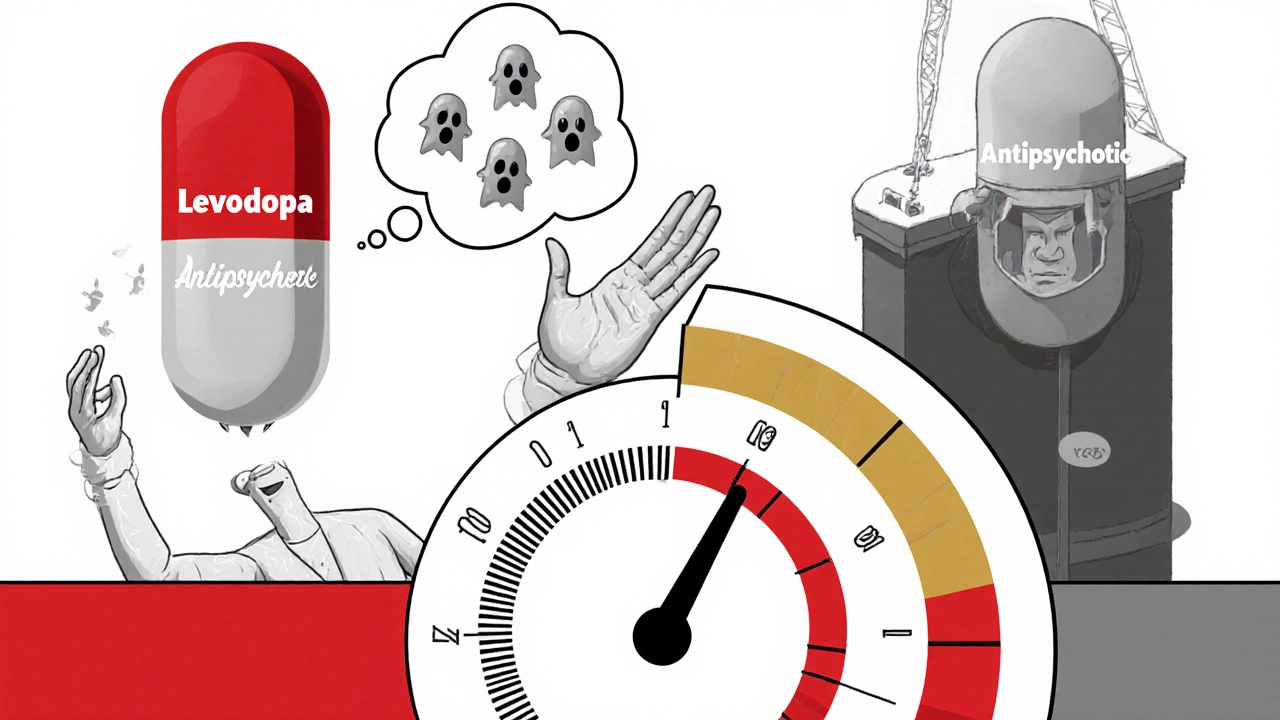

Imagine taking a medication to control your tremors, only to find your hallucinations get worse. Or taking a drug to quiet your mind, only to feel your body lock up. This isn’t a rare nightmare-it’s a daily reality for thousands of people caught between Parkinson’s disease and psychosis. The problem? Two common drug classes-levodopa and antipsychotics-work in opposite ways on the same brain chemical: dopamine. And when they meet, they don’t just cancel each other out. They make things worse.

How Levodopa Works (and Why It’s a Double-Edged Sword)

Levodopa is the gold standard for treating Parkinson’s disease. It doesn’t directly replace dopamine. Instead, it’s a building block your brain turns into dopamine. That’s crucial because dopamine can’t cross from your bloodstream into your brain-but levodopa can. Once inside, enzymes convert it into dopamine, helping restore movement control in the parts of the brain that have lost dopamine-producing cells.

But here’s the catch: as Parkinson’s progresses, your brain loses more and more of those natural dopamine factories. The remaining ones can’t regulate how much dopamine gets released. So even a normal dose of levodopa can cause wild swings-too little in the morning, too much by lunch. These spikes are what cause those uncontrollable jerks called dyskinesias. And here’s the kicker: the more advanced your Parkinson’s, the more sensitive your brain becomes to these surges. A dose that worked fine last year might now trigger severe side effects.

That’s why levodopa isn’t just a treatment-it’s a pharmacological rollercoaster. And when you add another drug that blocks dopamine, things get dangerous.

How Antipsychotics Work (and Why They’re a Problem for Parkinson’s Patients)

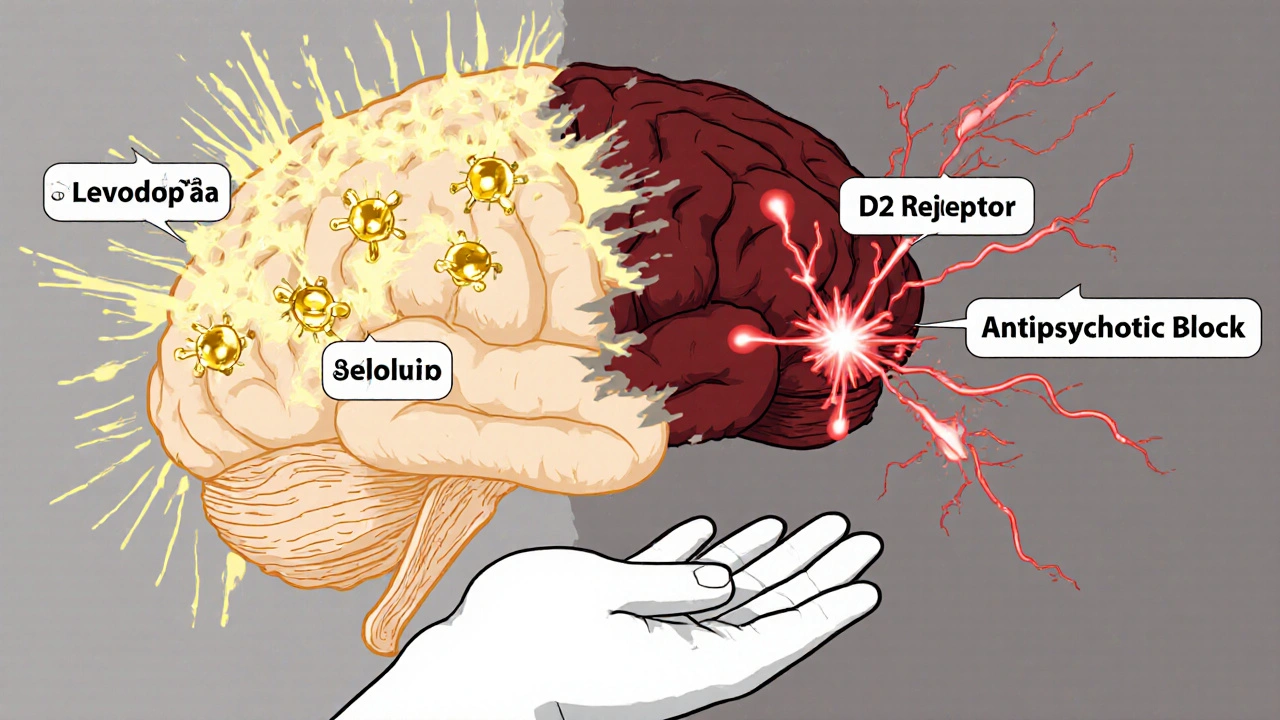

Antipsychotics like risperidone, haloperidol, and even quetiapine were designed to calm psychotic symptoms-hallucinations, delusions, paranoia. They do this by blocking dopamine receptors, especially the D2 type. In schizophrenia, too much dopamine activity in certain brain areas is thought to cause psychosis. So reducing dopamine signaling helps.

But in Parkinson’s, the problem is the opposite: too little dopamine in the motor control areas. When you block dopamine receptors there with an antipsychotic, you’re essentially turning down the signal your brain is already struggling to send. The result? Stiffness, slow movement, tremors-all the motor symptoms you were treating with levodopa suddenly get worse.

Studies show that even low doses of antipsychotics can increase Parkinson’s motor symptoms by 25-35% on standard rating scales. One 2015 study of 127 patients found that starting risperidone at just 0.5 mg/day led to a dramatic spike in UPDRS scores-sometimes within 72 hours. For many, it’s like trading one crisis for another.

The Therapeutic Trap: Treating One Condition Worsens the Other

This is the core conflict: levodopa tries to boost dopamine, antipsychotics try to block it. When someone has both Parkinson’s and psychosis-which happens in 30-40% of cases-the choices are brutal.

Give them levodopa? Their psychosis might flare up. Studies show 15-20% of schizophrenia patients develop worse hallucinations or delusions after taking levodopa. One 1988 trial found that giving just 300 mg of levodopa to schizophrenia patients triggered psychotic relapse in 60% of cases. That’s not a side effect-it’s a pharmacological model of psychosis.

Give them an antipsychotic? Their Parkinson’s gets worse. A 2022 survey of 150 movement disorder specialists found that 89% avoid traditional antipsychotics entirely. Even the “safer” ones like quetiapine still worsen movement in 30-50% of patients. One Reddit user, ParkinsonsWarrior2020, wrote: “My tremor went from 2/10 to 8/10 within two days of starting 0.25 mg quetiapine.” That’s not an outlier. It’s common.

And it’s not just about symptoms. Abruptly stopping levodopa-or suddenly starting a strong antipsychotic-can trigger neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS). This rare but deadly condition causes high fever, muscle rigidity, confusion, and organ failure. Mortality rates are 10-20%. The Cleveland Clinic confirms dopamine agonists can reverse NMS, which tells you everything: it’s a dopamine crisis.

What Doctors Do When There’s No Good Option

Most neurologists don’t want to choose between two bad outcomes. So they look for alternatives.

The only antipsychotic with FDA approval specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis is pimavanserin (Nuplazid). Unlike others, it doesn’t block dopamine. Instead, it targets serotonin receptors-specifically 5-HT2A. That’s why it doesn’t worsen movement. But it’s expensive, and even then, 42% of specialists say it still causes some motor decline in a third of patients.

Another option? Don’t treat the psychosis at all. A 2021 study found that 65% of Parkinson’s patients with psychosis get no specific treatment because doctors fear making motor symptoms worse. That’s not ideal-but it’s safer than the alternatives.

Some clinicians try very low doses of clozapine, but it carries a risk of severe motor worsening and requires weekly blood tests. Others avoid anticholinergics entirely-those drugs can worsen cognition and cause confusion in older patients.

The American Academy of Neurology recommends a 4-week washout period when switching between these drugs. But for someone with active hallucinations, waiting four weeks isn’t practical. That’s why many patients fall through the cracks.

New Hope: Drugs That Don’t Touch Dopamine

The future isn’t about tweaking dopamine-it’s about bypassing it entirely.

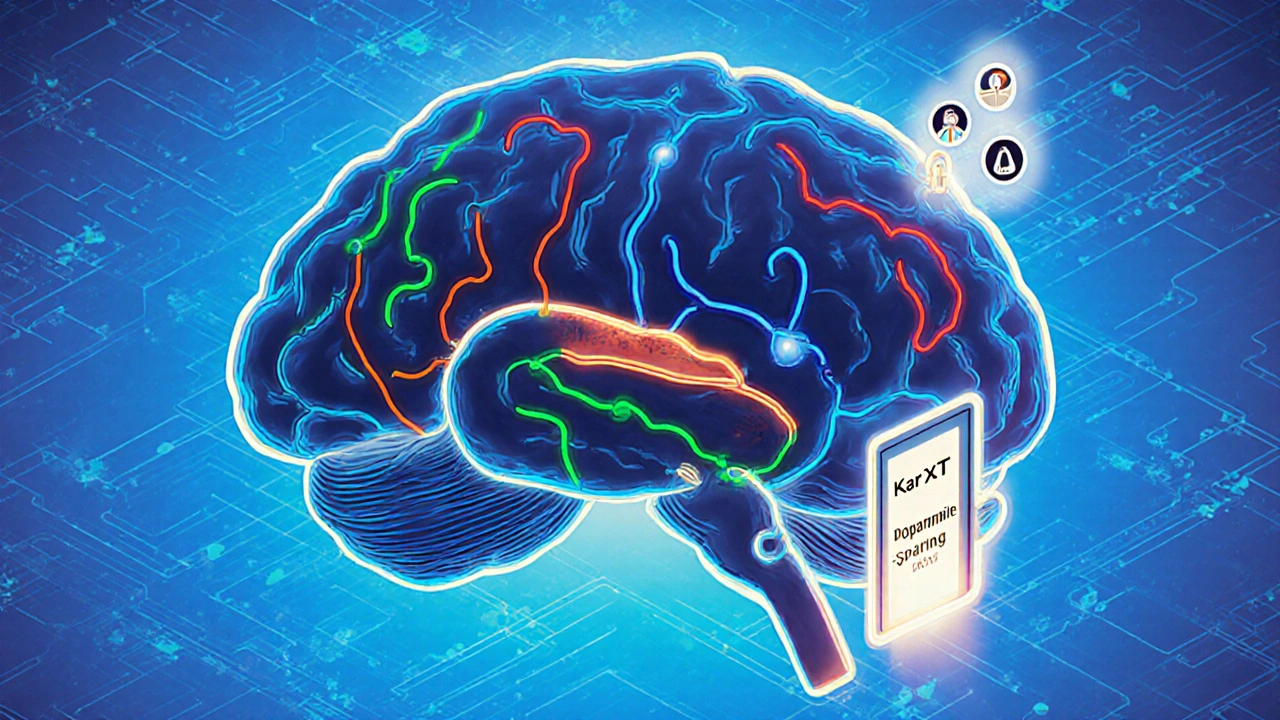

In May 2023, a phase 3 trial of KarXT (xanomeline-trospium) showed a 25% reduction in psychosis symptoms in Parkinson’s patients-with no worsening of movement. That’s huge. KarXT works by activating muscarinic receptors, not touching dopamine at all. It’s a completely different pathway.

Researchers at the Van Andel Institute are testing drugs that target alpha-synuclein-the misfolded protein that builds up in Parkinson’s brains. If they can clear that buildup, they might prevent psychosis from developing in the first place. Results are expected by late 2024.

The FDA now explicitly asks drug developers to design “dopamine-sparing” treatments. That’s a major shift. And big pharma is responding. The Parkinson’s psychosis market is projected to hit $2.3 billion by 2027. That’s not just profit-it’s recognition that the old model doesn’t work.

What Patients and Families Need to Know

If you or a loved one is on levodopa and starts showing signs of psychosis-seeing things that aren’t there, believing false ideas, becoming paranoid-don’t assume it’s just “Parkinson’s getting worse.” It might be the medication.

Don’t stop levodopa on your own. Abrupt withdrawal can trigger NMS. Don’t start an antipsychotic without consulting a movement disorder specialist. General neurologists often lack the training to handle this balance. Only 38% feel confident managing Parkinson’s psychosis, compared to 89% of specialists.

Keep a symptom log. Track motor function daily (tremor, stiffness, slowness) and mental state (hallucinations, confusion, agitation). A change of 10 points or more on UPDRS or PANSS scales is clinically meaningful. If motor symptoms worsen after starting an antipsychotic, speak up. Early intervention saves function-and sometimes lives.

Ask about pimavanserin. Ask about KarXT. Ask if a specialist can help. This isn’t a dead end. It’s a complex problem-and the solutions are evolving.

Why This Matters Beyond Parkinson’s

This isn’t just about Parkinson’s. It’s about how we think about brain chemistry. We used to believe dopamine imbalance was a simple on-off switch: too much = psychosis, too little = Parkinson’s. But the reality is messier. The same chemical can be too much in one brain region and too little in another. The same drug can help one person and harm another.

It’s why precision medicine is the future. Researchers are using PET scans to measure dopamine transporter levels before prescribing. If a patient’s striatal DAT binding is below 1.5 SUVr, they have an 80% risk of severe motor worsening with antipsychotics. That’s not guesswork-that’s data. And it’s changing how we treat.

The goal isn’t to find the perfect drug. It’s to find the right balance for the right person. And that balance is fragile. One pill can tip the scale. But with better tools, better drugs, and better awareness, we’re finally moving past the trap.

Can levodopa cause hallucinations in people without Parkinson’s?

Yes. While levodopa is primarily used for Parkinson’s, it’s sometimes prescribed off-label for conditions like restless legs syndrome or dopamine-responsive dystonia. In people with underlying psychiatric conditions-especially schizophrenia-levodopa can trigger or worsen hallucinations and delusions. Studies show up to 60% of schizophrenia patients experience psychotic relapse after taking 300 mg/day of levodopa, even if they’ve been stable for years.

Why can’t doctors just reduce levodopa to stop psychosis?

Reducing levodopa can make motor symptoms worse-sometimes severely. Parkinson’s patients rely on levodopa to walk, speak, and eat. Cutting the dose often leads to freezing, falls, and loss of independence. Many patients would rather live with hallucinations than lose their mobility. That’s why doctors avoid lowering levodopa unless absolutely necessary.

Are all antipsychotics equally dangerous for Parkinson’s patients?

No. First-generation antipsychotics like haloperidol are extremely risky and should be avoided. Second-generation drugs like quetiapine and clozapine are less likely to worsen movement-but they still do in many cases. Pimavanserin is the only one approved specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis because it doesn’t block dopamine receptors. Even then, it’s not risk-free.

What is neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and how is it linked to these drugs?

NMS is a life-threatening reaction to antipsychotics that causes high fever, muscle rigidity, confusion, and organ failure. It can occur when antipsychotics are started in Parkinson’s patients or when levodopa is suddenly stopped. The risk is small-0.01-0.02%-but mortality is 10-20%. It’s a dopamine crisis: too little dopamine signaling triggers a full-body stress response. Immediate treatment requires stopping the antipsychotic and giving dopamine agonists.

Is there a blood test to check if levodopa and antipsychotics will interact badly?

Not yet. But advanced imaging like DAT-SPECT scans can show how many dopamine transporters are left in the brain. Low levels (below 1.5 SUVr) predict a high risk of motor worsening with antipsychotics. Amyloid PET scans can also help identify patients more likely to develop psychosis from levodopa. These tools aren’t routine yet-but they’re becoming part of expert care.

Shante Ajadeen

November 11, 2025 AT 17:13This hit me hard. My mom’s been on levodopa for 8 years, and when they put her on quetiapine for hallucinations, she went from walking the hallway daily to needing a wheelchair in 3 days. No one warned us. We thought it was just the disease getting worse. Turns out, it was the med.

dace yates

November 12, 2025 AT 04:04I’ve been reading up on this since my dad got diagnosed. The part about pimavanserin being the only one approved for Parkinson’s psychosis really stood out. I didn’t even know there was a drug that didn’t mess with dopamine. Feels like a tiny win.

Danae Miley

November 13, 2025 AT 10:29Let’s be clear: the claim that ‘quetiapine is safer’ is dangerously misleading. A 2022 meta-analysis in Movement Disorders showed 47% of Parkinson’s patients on quetiapine had clinically significant motor decline within 14 days. The FDA label doesn’t even mention this. Doctors are still prescribing it like it’s harmless. This isn’t just a trade-off-it’s negligence.

Charles Lewis

November 13, 2025 AT 20:24It is imperative to recognize that the pharmacological dilemma presented herein is not merely a matter of drug interaction, but rather a profound reflection of the neurochemical heterogeneity inherent in the human brain. Dopamine, as a neurotransmitter, serves divergent physiological functions across distinct neural pathways-the nigrostriatal, mesolimbic, and mesocortical circuits-each of which operates under unique regulatory mechanisms. Consequently, the administration of levodopa, which elevates dopamine levels indiscriminately, may ameliorate motor deficits in the striatum while simultaneously exacerbating psychotic phenomena in the limbic system. Conversely, antipsychotics, which exert a broad antagonism at D2 receptors, may inadvertently silence motor signaling pathways already compromised by neurodegeneration. This dual-edged nature underscores the necessity for precision medicine approaches that account for individual neurochemical topography, rather than relying on one-size-fits-all pharmacological interventions.

Renee Ruth

November 15, 2025 AT 07:14They’re all just playing god with people’s brains. One day you’re told ‘this will help you walk,’ next day you’re told ‘this will stop you seeing ghosts.’ And when you cry because you can’t feed yourself anymore? They say ‘maybe it’s just the disease.’ Bullshit. It’s the meds. It’s always the meds. And nobody takes responsibility.

Samantha Wade

November 15, 2025 AT 22:15Shante, your story is so important. Thank you for sharing. I’m a nurse in a neuro clinic, and I see this exact scenario every week. We need to push for better education-both for families and for general neurologists. Pimavanserin isn’t perfect, but it’s the best tool we have right now. And KarXT? That’s the future. If your mom’s doctor hasn’t mentioned it, ask again. And if they say no, get a second opinion. You’re not overreacting-you’re fighting for her quality of life.

Elizabeth Buján

November 17, 2025 AT 11:24i just wanna say… this whole thing feels like our brains are these delicate glass sculptures and every pill is a hammer. we’re just trying to hold it all together. my aunt’s been on levodopa for 12 years and still smiles when she dances in her chair. she says the hallucinations are like old friends who won’t leave. but she’d give them up in a heartbeat if she could just tie her shoes again. no one talks about that part. the quiet grief of choosing between movement and peace.

Andrew Forthmuller

November 18, 2025 AT 02:35So… pimavanserin = no motor worsening? Then why’s it so expensive? And why don’t docs just use that first?

vanessa k

November 20, 2025 AT 00:04Andrew, that’s the exact question I’ve been asking. I called my mom’s neurologist last week. He said ‘it’s not covered by insurance unless you’ve tried everything else.’ Everything else = almost broke her. We spent 3 months trying quetiapine, then clozapine. She almost went to the hospital. Now we’re waiting on a prior auth for pimavanserin. It’s a joke. They act like it’s a luxury. It’s a lifeline.

manish kumar

November 21, 2025 AT 20:03As someone who works with Parkinson’s patients in India, I can tell you this problem is global. In our hospitals, we rarely have access to pimavanserin or even DAT-SPECT scans. Most families choose to stop levodopa because antipsychotics are cheaper and more available. The result? Patients freeze in bed, stop eating, and become dependent. We need global access-not just for the wealthy. This isn’t just science. It’s justice.