When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for a 30-day supply of metformin or lisinopril, it’s easy to think you’re getting a bargain. And in many ways, you are. But if you think that means the U.S. has cheap drugs overall, you’re missing the full picture. The truth is more complicated: generic drugs in America are often cheaper than in other rich countries, but brand-name drugs cost nearly five times more. This split creates a confusing reality - Americans pay less for the pills they take most often, but far more for the ones that cost the most.

Generics Are Cheaper in the U.S. - Here’s Why

Over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s higher than any other developed country. In places like Germany or France, generics make up less than half of prescriptions. This massive volume gives U.S. buyers leverage. When three or more companies start making the same generic drug, prices crash. According to FDA data from 2019, prices drop to just 15-20% of the original brand-name price when four or more manufacturers enter the market. In some cases, a pill that cost $100 as a brand-name drug ends up costing less than $2 as a generic.

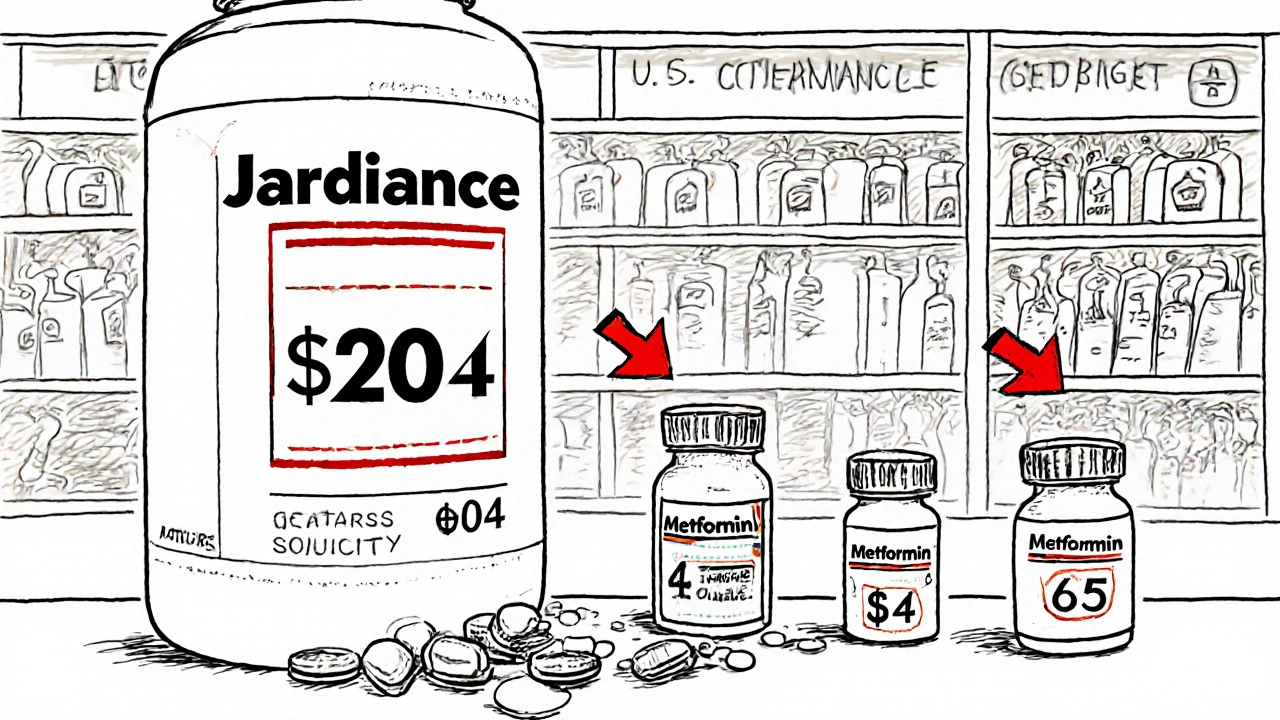

Compare that to countries like Canada or the U.K., where governments set price caps and limit the number of generic manufacturers allowed to compete. In those systems, there’s less pressure to slash prices. In the U.S., it’s a free-for-all. Pharmacies buy from the cheapest supplier. Mail-order services pit distributors against each other. Even Walmart and Costco offer $4 generic lists - something you won’t find anywhere else in the world at that scale.

That’s why a 30-day supply of amoxicillin costs $4 in the U.S. but $12 in Australia. Or why a month’s supply of atorvastatin runs $5 here and $18 in Japan. The RAND Corporation’s 2022 study found U.S. generic prices were 33% lower than in 33 other OECD countries. The FDA confirmed this again in 2023: the 773 new generic approvals that year saved the system an estimated $13.5 billion.

Brand-Name Drugs Are Where the U.S. Pays the Most

But here’s the catch: the other 10% of prescriptions - the brand-name ones - are where the U.S. stands out for all the wrong reasons. A single month’s supply of Jardiance, a diabetes drug, costs $204 in Medicare’s negotiated price. In Australia, it’s $52. Stelara, used for psoriasis and Crohn’s, costs $4,490 in the U.S. versus $2,822 in Germany. The Health System Tracker found that for nearly half of the first 10 drugs negotiated by Medicare, the U.S. price was more than three times what other countries pay.

Why? Because the U.S. doesn’t negotiate brand-name drug prices like other nations do. Most countries have centralized agencies that say, “This is what we’ll pay.” The U.S. lets drugmakers set their own list prices - and then relies on insurers and pharmacy benefit managers to negotiate discounts behind closed doors. The result? You see a high sticker price, but you rarely pay it. The real cost - what insurers and Medicare actually pay - is lower. But even after rebates, the U.S. still pays more than other countries for the same brand-name drugs.

A 2024 University of Chicago study found that when you look at net prices (after rebates), the U.S. actually pays less than Canada, Germany, and the U.K. for some drugs. But that’s only true because Medicare and Medicaid have massive buying power. For people without insurance, or with high-deductible plans, the list price is still the price they see at the counter. And that’s where the pain hits hardest.

Why Do Other Countries Pay So Little?

It’s not magic. It’s policy. Countries like France, Japan, and Australia use strict price controls. They set a maximum price for every drug based on its medical value, how much it costs to make, and what other countries pay. If a drugmaker doesn’t agree, the drug doesn’t get sold there. The U.S. doesn’t do that. Drugmakers can charge whatever they want - until someone with enough clout (like Medicare) steps in to negotiate.

Japan, for example, updates drug prices every two years. If a generic version comes out, they automatically cut the brand-name price. In France, the government refuses to reimburse drugs that don’t offer significant improvement over existing ones. That keeps prices down. In the U.S., if a new drug comes out - even if it’s only slightly better - it can cost tens of thousands of dollars a year.

The result? Americans pay more for innovation. But they also fund it. The U.S. accounts for nearly half of global pharmaceutical spending. That money pays for research, clinical trials, and development. Other countries benefit from those breakthroughs without paying the same price. Some experts argue this is “free riding.” Others say it’s fair - if you can’t afford a drug, you shouldn’t have to pay for someone else’s R&D.

What Happens When There’s No Competition?

There’s a dark side to the U.S. generic system: when competition disappears, prices spike. The FDA has documented cases where a generic drug had three manufacturers - then two left the market. Suddenly, only one company was left. And they raised the price by 500% or more. This happened with doxycycline, a common antibiotic. In 2013, it cost $20 a month. By 2015, it was $1,800. Why? Because no one else was making it.

That’s why regulators now watch generic markets closely. If a drug has only one or two makers, they move faster to approve new applicants. The FDA’s goal is to prevent monopolies. But it’s a constant game of catch-up. And when it fails, patients pay the price.

How Medicare’s New Negotiations Fit In

In 2022, Congress gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for the most expensive drugs. The first 10 were announced in 2023. The results? Medicare paid less than the U.S. list price - but still more than most other countries. In every case except one (Stelara in Germany), the other countries paid less. That tells you something: even the U.S. government can’t bring prices down to global levels.

The next round of 15 drugs is due by February 2025. These include more high-cost treatments for cancer, heart disease, and autoimmune conditions. The pharmaceutical industry says this will kill innovation. But the data doesn’t back that up. Countries like Germany and Japan have had price controls for decades - and still produce more new drugs per capita than the U.S.

What This Means for You

If you take generics, you’re winning. You’re paying less than people in most other countries. Use GoodRx, Blink Health, or your local pharmacy’s discount program. You can often get a 30-day supply of most generics for under $10 - sometimes under $5.

If you take brand-name drugs, you’re in the crosshairs. Check if your drug is on Medicare’s negotiation list. Ask your doctor if a generic or biosimilar exists. Call your insurer - sometimes they’ll cover a different version at a lower cost. And if you’re paying full price? You’re being charged the U.S. list price - the highest in the world.

There’s no single fix. But understanding the split - cheap generics, expensive brands - helps you make smarter choices. The system isn’t broken. It’s just uneven. And if you know where the savings are, you can use them.

Amy Hutchinson

November 26, 2025 AT 01:38Archana Jha

November 27, 2025 AT 21:35Aki Jones

November 29, 2025 AT 07:19Jefriady Dahri

November 29, 2025 AT 13:49Sharley Agarwal

November 30, 2025 AT 18:24Shivam Goel

December 1, 2025 AT 11:03Leisha Haynes

December 3, 2025 AT 02:26Kimberley Chronicle

December 5, 2025 AT 01:20Shirou Spade

December 6, 2025 AT 17:41Lisa Odence

December 8, 2025 AT 08:47