When you see an FDA safety alert about a medication you or someone you know is taking, it’s easy to panic. The headline says "Potential Link to Liver Injury" or "Risk of Severe Skin Reaction" - and suddenly, your prescription feels dangerous. But here’s the truth: an FDA safety announcement is not a warning to stop taking your medicine. It’s a signal - one that needs context, not fear.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration doesn’t issue these alerts lightly. Every Drug Safety Communication is the result of months, sometimes years, of data review. They pull from over 25 million adverse event reports in the FAERS database, clinical trial results, peer-reviewed studies, and real-world patient experiences. But raw data doesn’t tell the whole story. What matters is how you read it.

Understand the Difference Between an Event and a Reaction

Not every bad thing that happens after taking a drug is caused by the drug. The FDA makes this distinction clear: an adverse event is any medical problem that occurs after taking a medication - whether it’s related to the drug or not. A serious adverse drug reaction is something the FDA believes is reasonably linked to the drug’s pharmacological action.

For example, if someone takes a blood pressure medication and then has a heart attack two weeks later, that’s an adverse event. But if 500 other patients on the same drug have heart attacks at a rate three times higher than those on a placebo, and the pattern holds across multiple studies, that’s a signal of a possible adverse drug reaction. The FDA looks for patterns - not single cases.

That’s why you’ll often see phrases like "potential signal" or "possible association" in these alerts. The FDA isn’t saying the drug causes the problem. They’re saying: "We’ve seen something unusual. We’re looking into it. Don’t stop your medicine yet."

Check the Timing: Is This New Information?

Before you react to an alert, ask: "Is this something we didn’t know before?" The FDA only issues safety communications about new safety information - meaning data that emerged after the drug was approved. Clinical trials involve thousands of patients. But real-world use involves millions. That’s where rare side effects show up.

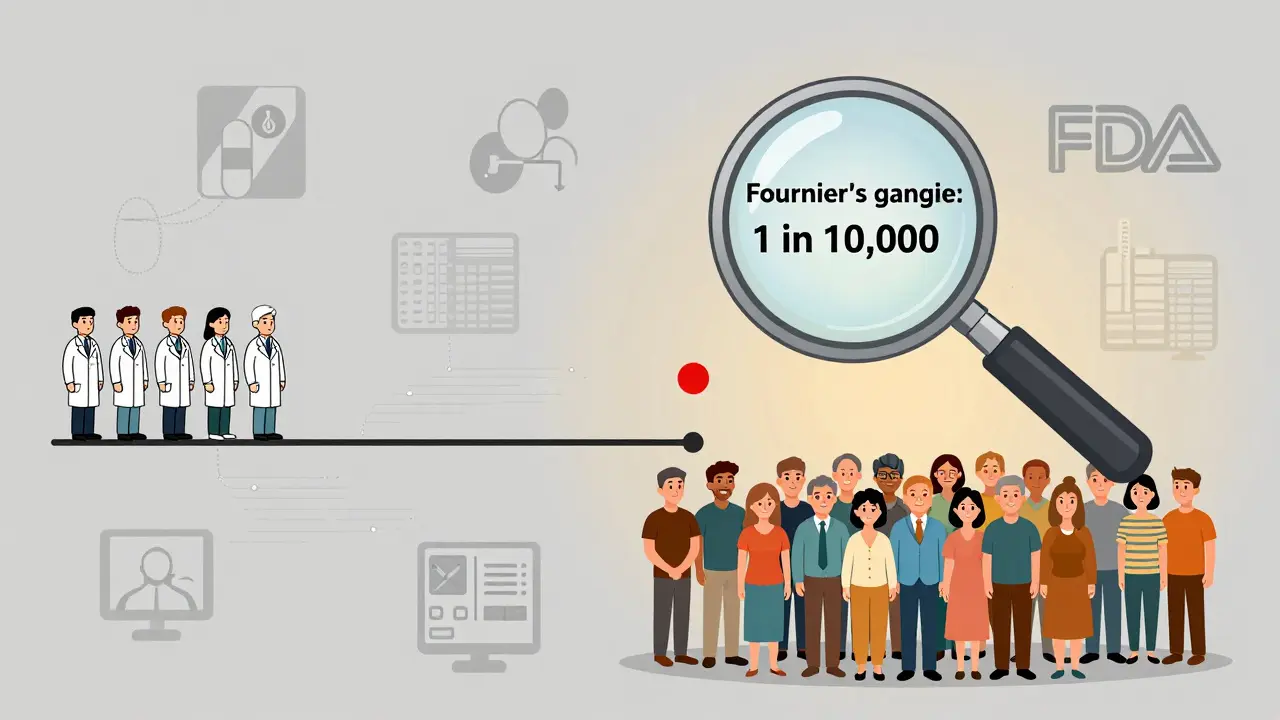

Take SGLT2 inhibitors, a class of diabetes drugs. During trials, Fournier’s gangrene (a rare but deadly infection) was seen in fewer than 1 in 10,000 patients. After approval, as millions more started taking the drug, the rate climbed to about 0.2 cases per 1,000 patient-years. That’s still extremely rare - but the FDA had to update the label because the risk was real and previously underestimated.

When an alert says "this risk was not identified during clinical trials," it’s not a red flag. It’s a sign the system is working. Post-market surveillance catches what controlled studies miss.

Look for the Numbers - Not Just the Warnings

The most misleading part of FDA alerts? They often don’t give you the numbers. But the best ones do.

Compare these two statements:

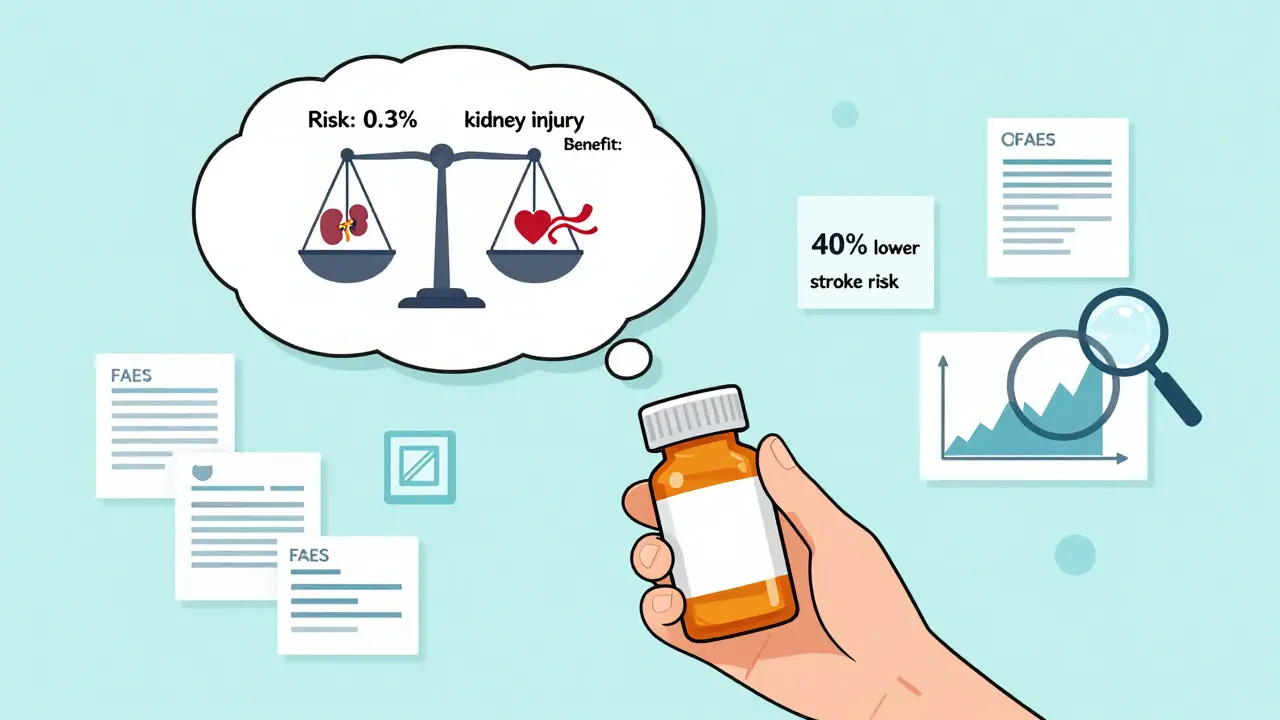

- "This drug may increase the risk of kidney injury."

- "In patients with Type 2 diabetes, this drug increases the risk of kidney injury from 0.1% to 0.3% over five years."

The second one tells you something useful. The absolute risk went from 1 in 1,000 to 3 in 1,000. That’s a 200% relative increase - which sounds scary. But in absolute terms, it’s still very low. If you’re managing diabetes, the benefit of preventing heart attacks, strokes, and kidney failure likely far outweighs that tiny increase in risk.

Dr. Robert Temple, former FDA deputy director, put it plainly: "The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." But the reverse is also true: a signal isn’t proof. Always ask: "What’s the baseline risk? What’s the benefit?"

Consider Your Condition and Alternatives

Not all risks are equal. A 1 in 10,000 chance of a serious skin reaction might be unacceptable for someone taking acne medication. But for someone with advanced melanoma and no other treatment options, that same risk might be worth it.

The FDA’s 2024 Benefit-Risk Assessment guidance now requires evaluating six key factors:

- How severe is the condition being treated?

- Are there other effective treatments available?

- How large is the benefit?

- How frequent and severe is the risk?

- Can the risk be managed?

- What do patients say about their experience?

For example, in oncology, drugs with high toxicity are often approved because the alternative is death. In depression, a small increase in suicidal ideation risk might be acceptable if the drug lifts someone out of a life-threatening state. The risk-benefit balance is personal. It’s not one-size-fits-all.

Don’t Panic - But Don’t Ignore It Either

Here’s what the FDA says in nearly every alert: "This communication does not mean you should stop taking the medication."

That’s critical. In 2022, a survey of 1,200 physicians found that 42% changed their prescribing habits after an FDA alert - only to later find the risk was minimal. Patients, too, often stop their meds out of fear. One study showed 75% of patients who read a safety alert felt confused about whether to keep taking their drug.

But stopping a medication without talking to your provider can be dangerous. Withdrawal from antidepressants can trigger severe depression. Stopping blood thinners can cause strokes. Antihypertensives? Sudden discontinuation can spike blood pressure to dangerous levels.

So what should you do? First, read the full alert on the FDA website. Look for the "Recommendations" section. Then, call your doctor or pharmacist. Bring the alert with you. Ask: "Is this risk real for me? Is it higher because of my age, other conditions, or other drugs I’m taking?"

Use the FDA’s Tools - and Know Their Limits

The FDA has made big improvements in how they communicate risk. Their 2023 draft guidance introduced flowcharts to help clinicians determine if an adverse event should be reported. They’re also testing a patient-facing visualization tool set to launch in early 2026 - one that will show risk in simple graphics, like a bar chart comparing the chance of side effects to the chance of benefit.

But tools aren’t perfect. A 2022 BMJ analysis found that only 58% of FDA Drug Safety Communications clearly labeled whether a finding was a "potential signal" or a "confirmed risk." That’s a gap. And many alerts still lack quantitative data. That’s why expert opinions matter. Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of the FDA’s drug center, said it best: "Risk-benefit is not a calculation. It’s a judgment."

That judgment requires you to be informed. You don’t need to be a scientist. But you do need to ask the right questions.

What to Do When You See an FDA Alert

Here’s a simple five-step process:

- Don’t stop your medicine. The FDA almost never recommends immediate discontinuation in initial alerts.

- Find the original alert. Go to fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability and search by drug name. Read the full text - not just the headline.

- Look for numbers. Is there a rate? A comparison? If not, ask your provider: "What’s the actual risk?"

- Ask about alternatives. "If this drug has a risk, what are my other options? Are they safer? Better?"

- Decide together. Your provider should help you weigh the risk against the benefit - not make the decision for you.

Remember: the FDA’s job isn’t to scare you. It’s to give you information so you can make better choices. The system isn’t perfect - but it’s the most robust drug safety network in the world. And it’s designed to protect you, not alarm you.

Does an FDA safety alert mean the drug is dangerous?

No. An FDA safety alert means the agency has seen a pattern in reports that warrants closer review. It does not mean the drug causes the problem, nor does it mean you should stop taking it. Many alerts turn out to be false signals, and even confirmed risks often affect only a tiny fraction of users. The FDA’s job is to investigate, not to panic the public.

How often does the FDA issue safety alerts?

The FDA issues about 40 to 50 Drug Safety Communications each year - roughly one every 7 to 10 days. Most are routine updates based on new data. Only about 65% result in labeling changes, 20% lead to new risk management plans (REMS), and 15% trigger further studies. Most alerts don’t change how a drug is used.

Can I trust the data in FDA alerts?

The data comes from real-world reports, but it’s not perfect. FAERS receives over 1.2 million reports annually - many are incomplete, inaccurate, or unrelated to the drug. The FDA uses statistical methods to spot patterns, but they can’t confirm causation from reports alone. That’s why they call them "potential signals" until more evidence is gathered.

Why do some drugs get alerts years after approval?

Clinical trials involve thousands of patients over months or a few years. Real-world use involves millions of people over decades. Rare side effects - like one in 10,000 or even one in 100,000 - only show up after long-term use. That’s why post-market surveillance is essential. It’s not a failure of approval - it’s how safety science works.

Should I avoid a drug just because it has an FDA alert?

No. Many life-saving drugs have safety alerts. The key is whether the benefit outweighs the risk - for you. A drug with a 0.1% risk of liver injury might be the only option for someone with a deadly infection. Never make a decision based on fear. Talk to your provider. Use the alert as a starting point for a conversation, not a reason to stop treatment.

What’s the difference between an FDA alert and a drug recall?

An FDA alert is a warning or recommendation based on emerging data. A recall is a formal action to remove a drug from the market because it’s proven to be unsafe, contaminated, or ineffective. Recalls are rare. Alerts are common. Most alerts lead to updated labels, not removal.

Final Thought: Your Doctor Is Your Best Resource

Drug safety isn’t about avoiding risk. It’s about managing it. Every medication carries some risk - even aspirin. The goal isn’t zero risk. It’s the best possible balance between benefit and harm. The FDA gives you the data. Your provider helps you interpret it. You bring your values, your health history, and your goals. Together, you make the call.

Don’t let a headline make your decision for you. Ask questions. Demand clarity. And remember - the system works best when you’re informed, not afraid.

Christina Widodo

January 12, 2026 AT 20:16Okay but like, why do these alerts always sound like a horror movie trailer? I read one about my antidepressant and my heart started pounding like I’d been diagnosed with something terminal. Then I actually read the full thing and it was like, ‘0.02% chance of a rash that goes away in a week.’ I just needed someone to translate the fear into facts.

Alice Elanora Shepherd

January 14, 2026 AT 18:56Thank you for this. As a pharmacist, I see patients panic over these alerts all the time. The FDA doesn't say 'stop'-they say 'pay attention.' Most people don't realize that the very system designed to protect them is the same one that flagged thalidomide in the '60s, or Vioxx in the '00s. It's not perfect, but it's the best we've got. Please, if you're worried-call your provider. Don't just Google it and self-diagnose a crisis.

Cassie Widders

January 15, 2026 AT 12:01My grandma stopped her blood pressure med after an alert. Ended up in the ER. She didn't understand the difference between 'possible link' and 'proven danger.' This post should be mandatory reading for anyone over 60.

Darryl Perry

January 17, 2026 AT 11:09Prachi Chauhan

January 18, 2026 AT 13:19Look, I get it. We're scared of pills. But think about it-our bodies are walking chemical factories. Every bite of food, every breath of air-it's all risk. The real question isn't 'is this drug dangerous?' It's 'is this drug more dangerous than not taking it?' If you're diabetic and your A1c is 9.5, a 0.3% kidney risk is like worrying about a mosquito bite while standing in a hurricane.

Rinky Tandon

January 19, 2026 AT 15:00Y’all are being too nice. This is corporate cover-up. The FDA is owned by Big Pharma. They only alert when they HAVE to. They knew about the liver damage for YEARS. They just didn’t want to lose billions. Stop trusting the system. Start trusting your gut. I’ve seen people die because they listened to ‘experts.’

Ben Kono

January 21, 2026 AT 04:53Windie Wilson

January 21, 2026 AT 08:34Oh wow. So the FDA is like a TikTok algorithm that only sends you scary headlines because they get more clicks? I love how they say 'don't panic' while the whole thing is written like a thriller novel. Next they'll release a 10-page PDF titled 'Why Your Aspirin Might Be Secretly Plotting Against You.' 😭

Katherine Carlock

January 23, 2026 AT 03:57My mom’s on a drug with an alert. I sat with her for an hour, printed out the FDA page, and we went through the numbers together. She cried. Not from fear-from relief. She realized she wasn’t alone in worrying, and that someone had actually taken the time to explain it. That’s what this post does. Thank you.

Konika Choudhury

January 24, 2026 AT 09:11