When a brand-name drug loses patent protection, the race to sell the first generic version begins. But here’s the twist: the company that makes the original drug can also launch its own generic version - and it often does, right when the first generic hits the market. This isn’t a mistake. It’s a strategy. And it changes how much you pay for your meds.

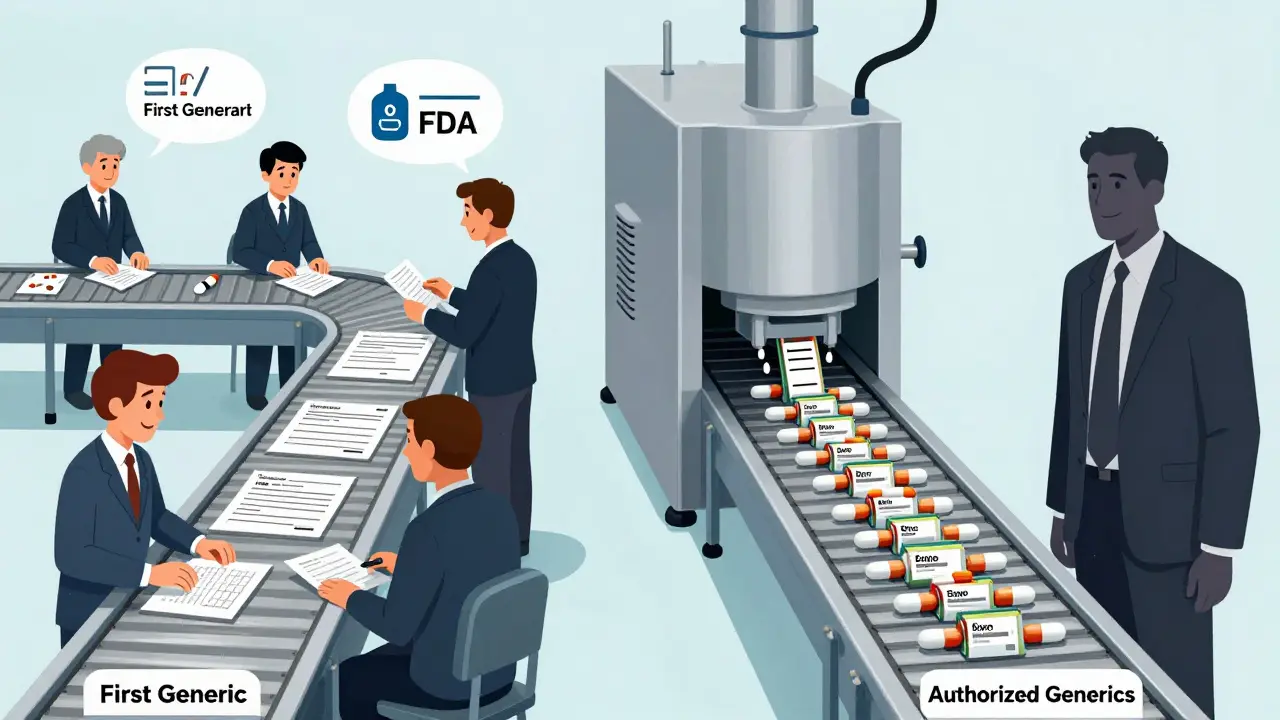

What’s the difference between a first generic and an authorized generic?

A first generic is made by a company that spent years challenging the brand’s patent, filed a full application with the FDA, proved its drug works the same way, and won the right to be the first to sell a cheaper version. That company gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell that generic - no one else can legally sell the same version during that time. In return, they’re supposed to get big rewards: often 70-90% of the market, with prices dropping 80-90%.

An authorized generic is different. It’s made by the brand company itself - or a partner they’ve licensed - using the exact same factory, same ingredients, same packaging. The only difference? It doesn’t carry the brand name. It’s sold as a generic, but it’s still the original manufacturer behind it. And here’s the key: they don’t need FDA approval through the normal generic process. They can launch it anytime.

That’s the problem. The first generic company spends millions and waits years to get to market. The brand company can launch its authorized generic the same day - or even before - and split the market.

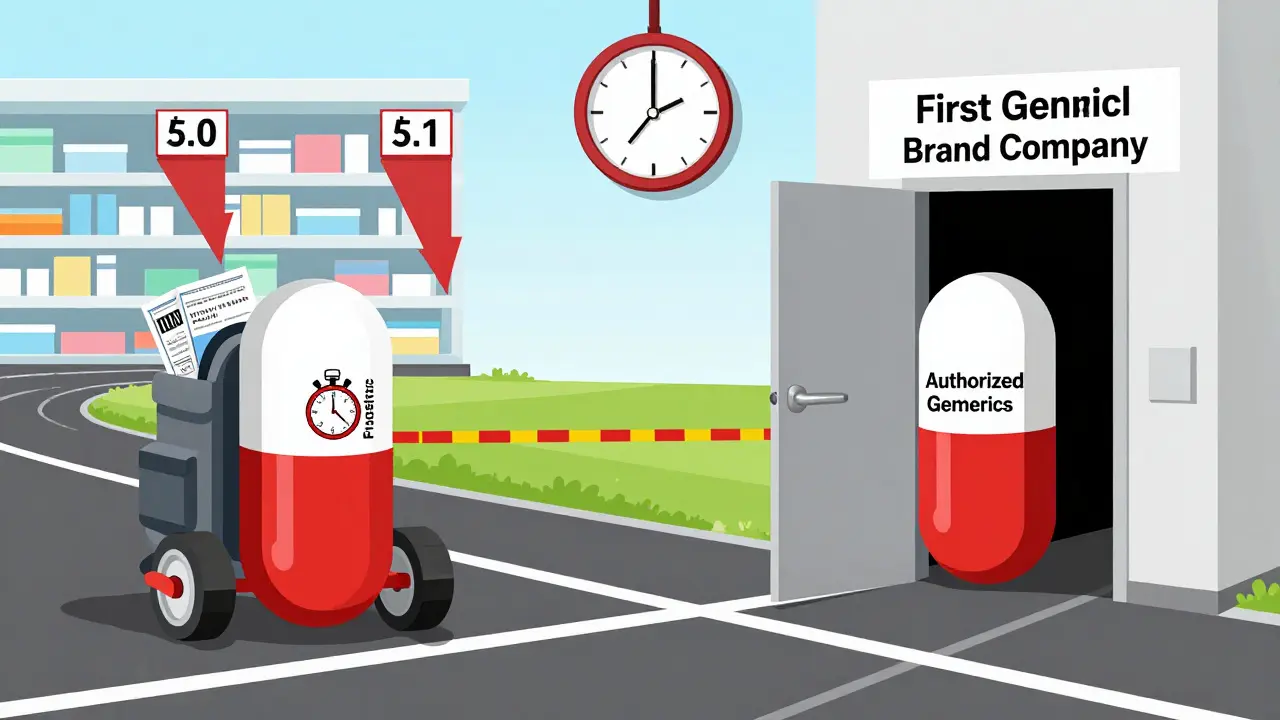

How timing kills the first generic’s advantage

The 180-day exclusivity period was meant to reward the brave company willing to take on the legal battle. But in practice, it’s become a trap.

Between 2010 and 2019, 73% of authorized generics launched within 90 days of the first generic’s approval. More than 40% hit the market on the exact same day. That’s not coincidence. That’s planning.

Take Lyrica (pregabalin). Pfizer’s brand drug was losing patent protection in 2019. Teva, a generic manufacturer, spent years preparing its version. When Teva launched, Pfizer immediately rolled out its own authorized generic under the Greenstone label. Within weeks, Pfizer’s version captured 30% of the generic market. Teva’s expected $300 million in exclusivity revenue? Cut in half.

This happens again and again. For drugs like Lipitor, Neurontin, and Prilosec, the brand companies didn’t wait. They jumped in fast. And when they do, the price drop isn’t 85%. It’s more like 65-75%. That means patients and insurers pay more than they should.

Why does the brand company do this?

Because they can. And because it’s profitable.

Brand companies don’t need to retest the drug. They already have the FDA-approved formula. They don’t need to hire lawyers for patent fights. They don’t need to build new factories. They just flip a switch: make the same pill, slap a generic label on it, and sell it at a discount.

It’s like opening a second store right across the street from your competitor’s new location - except you own the building, the inventory, and the delivery trucks.

For the brand company, it’s a win-win. They keep market share. They keep revenue. They avoid the stigma of being the “expensive” option. And they make it nearly impossible for the first generic to earn back its investment.

Who wins? Who loses?

The first generic manufacturer loses. They spent $5-10 million and 2-3 years preparing for this moment. Now they’re competing against the very company they tried to beat.

Patient savings shrink. Instead of 90% price drops, you get 70%. That’s still a discount - but not the full discount Congress intended when it passed the Hatch-Waxman Act in 1984.

The system loses too. The whole point of the 180-day exclusivity was to encourage more companies to challenge patents. But when the reward gets ripped away by the brand company’s own version, fewer generics take the risk. Fewer challengers mean fewer drugs get cheaper, faster.

And the brand company? They keep control. They keep profits. And they keep the market from turning fully generic.

The regulatory blind spot

The FDA approves both types of drugs. But they treat them the same on paper - even though they’re not the same in practice.

First generics go through a 10-month review process on average, sometimes stretching to three years if the FDA is backed up. Authorized generics? They can launch in days. No review needed. Just a label change.

In 2022, Congress finally took notice. The Inflation Reduction Act said authorized generics aren’t considered true generic competitors when calculating Medicare drug prices. That’s a small step - but it’s recognition that these aren’t normal generics. They’re a tactic.

Still, the FDA hasn’t changed its rules. Authorized generics are still allowed. The FTC has investigated pay-for-delay deals that sometimes go hand-in-hand with these launches, but enforcement is rare.

Meanwhile, generic manufacturers are adjusting. Some now avoid patent challenges on drugs where the brand company has a history of launching authorized generics. Others are building faster launch pipelines, hoping to get to market before the brand can react.

What’s next for generic drugs?

By 2027, authorized generics could make up 25-30% of all generic prescriptions - up from 18% in 2022. That’s not growth. That’s a shift in the game.

Drugs like Eliquis and Jardiance are now battlegrounds. Brand companies are watching for patent expirations and preparing authorized versions before the first generic even files.

For patients, this means you might see two generic versions of the same drug side by side on the pharmacy shelf. One made by a small company that fought the patent. The other made by the brand - identical, but cheaper because it doesn’t have to pay for legal battles.

But here’s the catch: if you pick the brand’s version, you’re not saving as much as you think. The brand company still controls the price. And they’re not in a rush to drop it further.

The real savings come when multiple independent generics enter the market. But when the brand company owns one of them, that competition never fully happens.

What should you do?

If you’re on a generic drug, ask your pharmacist: Is this an authorized generic? You might be surprised. Sometimes the same pill is sold under two different labels - one from the brand, one from a third-party manufacturer.

If you’re paying out of pocket, compare prices. Sometimes the authorized generic costs more than the independent generic - because the brand company doesn’t need to compete as hard.

If you’re on insurance, ask your plan if they prefer one version over another. Some plans still favor the first generic because they know it drives down prices faster.

And if you’re a patient who relies on these drugs, know this: the system isn’t broken. It’s being manipulated. The rules were made to help you. But the players changed the game.

Patty Walters

January 8, 2026 AT 19:30So the brand companies just wait for someone else to do all the hard work, then swoop in with the exact same pill and steal the spotlight? That’s not capitalism, that’s corporate theft. I’ve been on generic Lipitor for years and had no idea my ‘cheap’ version was made by Pfizer. Mind blown.

tali murah

January 10, 2026 AT 02:25Let me get this straight - the FDA lets a company that spent billions developing a drug launch a ‘generic’ version with ZERO review, while a smaller company spends years and millions just to get approved? This isn’t a loophole. It’s a rigged game designed to enrich shareholders and screw patients. And Congress just gave Medicare a Band-Aid. Pathetic.

Diana Stoyanova

January 11, 2026 AT 17:54Okay but imagine being Teva - you spend 3 years, hire lawyers, build labs, risk everything - and then Pfizer just flips a switch and drops their version on the same day. It’s like training for the Olympics for a decade, then watching the guy who owns the track show up with your exact shoes and win. And now you’re broke. This isn’t business. It’s psychological warfare disguised as market competition. We need real reform, not more jargon.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 11, 2026 AT 22:39This is why India is the pharmacy of the world - we don’t play these games. Our generics are real, cheap, and made by companies that actually fought for access. Meanwhile, American pharma just rebrands their own product and calls it ‘competition.’ Shameful. If you’re paying for a ‘generic’ in the US and it’s not from a real challenger, you’re being scammed.

Lindsey Wellmann

January 12, 2026 AT 04:38So… authorized generics are basically brand drugs in a tuxedo pretending to be a regular guy at the grocery store? 😒💸

Gregory Clayton

January 12, 2026 AT 05:12Of course the big pharma boys do this - they own the whole damn system. They write the laws, they fund the politicians, they even control the FDA. You think this is an accident? Nah. It’s by design. America’s healthcare isn’t broken - it’s working exactly how they planned. Screw the little guy.

Heather Wilson

January 14, 2026 AT 02:44Let’s quantify this: 73% of authorized generics launch within 90 days of first generic approval. 40% on the same day. That’s not ‘timing,’ that’s collusion. And the FTC’s inaction? A regulatory failure of epic proportions. The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to incentivize challenge, not enable predation. The data is clear. The moral is obvious. The enforcement? Nonexistent.

Jeffrey Hu

January 14, 2026 AT 15:06Actually, you’re all missing the real issue - it’s not the authorized generic, it’s the 180-day exclusivity window itself. That’s the real market distortion. It creates a monopoly that disincentivizes further competition. If you want true price drops, you need multiple generics entering at once - not one winner takes all. The system’s broken because it rewards delay, not innovation.

Ian Long

January 15, 2026 AT 20:24I get why the brand companies do it - they’re not evil, they’re just following the rules. But the rules are broken. We need a new framework: maybe require authorized generics to wait 60 days after first generic launch, or cap their market share at 20%. Not punishment - just fairness. Let the real challengers breathe.

Maggie Noe

January 16, 2026 AT 02:36Think about it - if the brand company can just slap a generic label on their own product, why would any new company ever risk the legal battle? The whole incentive structure is inverted. We’re not just losing price competition - we’re losing the spirit of innovation. The system was built to empower challengers. Now it’s built to silence them. And we’re all paying for it, one prescription at a time.

Johanna Baxter

January 17, 2026 AT 22:05I cried when I found out my generic Adderall was made by Teva. Then I found out the cheaper one next to it was Pfizer’s. I felt betrayed. Like I was the sucker who paid extra for the ‘real’ one. 😭

Ashley Kronenwetter

January 18, 2026 AT 12:21It is imperative to note that the FDA’s regulatory framework, while technically compliant with statutory requirements, fails to account for the economic and competitive implications of authorized generic market entry. The absence of differentiated labeling or disclosure requirements constitutes a significant information asymmetry for consumers and payers alike. Structural reform is not merely advisable - it is ethically imperative.

Angela Stanton

January 19, 2026 AT 15:50Authorized generics = brand-name drugs with a ‘generic’ SKU. The FDA’s AB rating system doesn’t distinguish between them, so pharmacists can’t even flag it. Meanwhile, PBMs are incentivized to push the cheapest SKU - which is often the authorized one, because the brand company gives them a better rebate. So patients get the ‘cheaper’ version… but the brand still pockets the profit. It’s a three-way shell game.

Jerian Lewis

January 20, 2026 AT 12:27People act like this is new. It’s not. It’s been happening since the 90s. The only difference now is we have data to prove it. And still, nothing changes. Because the people who profit from this? They’re the ones writing the laws. You think a senator’s kid is paying $200 for Eliquis? No. They’re on the authorized generic. And they don’t care.

Phil Kemling

January 21, 2026 AT 14:58It’s not just about drugs. It’s about trust. We’re told capitalism rewards risk. But here, the risk-taker gets crushed by the entity they challenged. The system doesn’t punish fraud - it rewards mimicry. And when the original innovator becomes the fastest imitator, what does that say about our values? Are we building a society where the only winning move is to copy, not create?