Postpartum Estrogen Risk Calculator

Estimate the safety level of ethinylestradiol-based birth control during breastfeeding based on weeks postpartum.

Risk Assessment

Quick Takeaways

- Ethinylestradiol is a synthetic estrogen used in many birth‑control pills.

- Only a tiny fraction (0.01‑0.03%) of the dose passes into breast milk.

- Most health agencies say it’s safe after the first 6 weeks postpartum.

- Progesterone‑only methods or non‑hormonal options are safer in the early weeks.

- Watch for infant fussiness, poor weight gain, or maternal nipple pain - they may signal a problem.

What is Ethinylestradiol a synthetic estrogen found in most combined oral contraceptives (COCs)?

Ethinylestradiol (EE) mimics the body’s natural estrogen, estradiol, but it’s more potent and has a longer half‑life. A standard COC contains 20‑35µg of EE plus a progestin. Because it’s chemically stable, EE survives the stomach and reaches the bloodstream, where it suppresses ovulation.

Key attributes:

- Chemical name: 17α-ethynylestradiol

- Typical dose in pills: 20‑35µg

- Half‑life: ~24hours

- Metabolism: Liver (CYP3A4)

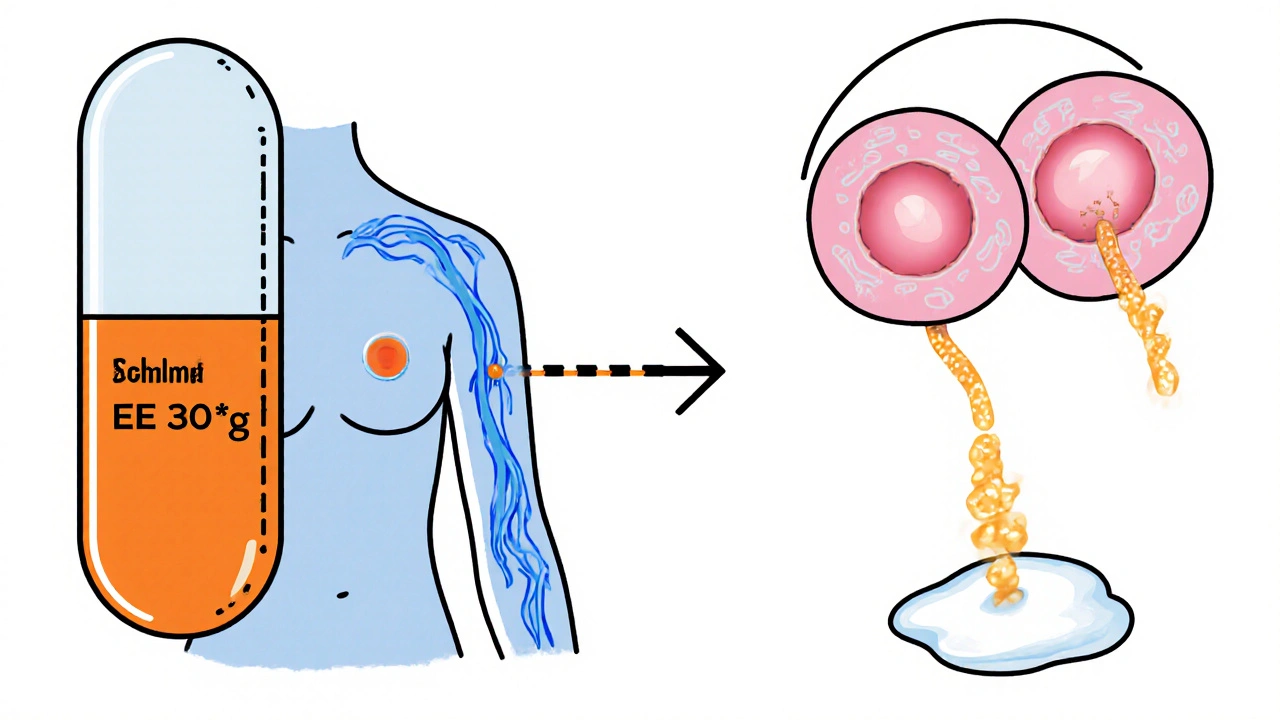

How EE Gets Into Breast Milk

When a nursing mother takes a COC, EE circulates in the plasma and can cross the mammary alveolar cells. The transfer is governed by two main factors:

- Maternal plasma concentration - higher doses mean more EE available for secretion.

- Lipid solubility - EE is lipophilic, so it partitions into the milk fat.

Studies from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) report a milk‑to‑plasma (M/P) ratio of 0.01‑0.03 for EE. In practical terms, a mother who takes a 30µg pill contributes roughly 0.3‑0.9µg of EE to each liter of milk - a dose far below any level that could affect infant growth.

Effects on Milk Production and Infant Exposure

Estrogen can suppress prolactin, the hormone that drives milk synthesis. However, the amount of EE that reaches the infant is so minuscule that most mothers see no change in supply. Research involving over 200 lactating women found:

- No statistically significant drop in daily milk volume.

- Infant weight gain remained within normal percentiles.

- Placental transfer of EE is lower than that of natural estradiol.

If a mother starts a COC before six weeks postpartum, a small subset (<5%) may notice slightly delayed lactogenesis II (the onset of copious milk). The effect is usually temporary and resolves when the infant’s own endocrine system matures.

Safety Guidelines for Nursing Moms

Both the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) and WHO recommend waiting until at least 6weeks after birth before starting a COC containing EE. The reasoning is two‑fold:

- The infant’s liver is still developing, making it more sensitive to any hormone exposure.

- Early milk production is most vulnerable during the first few weeks.

If contraception is needed sooner, consider these alternatives:

- Progestin‑only pill (POP) - no estrogen, virtually no transfer to milk.

- Implant (e.g., Nexplanon) - long‑acting, safe from day1 postpartum.

- Contraceptive patch or ring - lower systemic estrogen levels than pills, but still best after 6weeks.

- Non‑hormonal methods - condoms, copper IUD (the copper IUD can be inserted immediately after delivery).

Comparing Hormonal Options for Breastfeeding Moms

| Method | Estrogen Dose (µg) | Typical Start Time Post‑Delivery | Milk Transfer % (M/P) | Recommended for Early Lactation? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined Oral Contraceptive | 20‑35 | ≥6weeks | 0.01‑0.03 | No (wait 6weeks) |

| Progestin‑Only Pill | 0 | Day1 | ~0 | Yes |

| Implant (Etonogestrel) | 0 | Day1 | ~0 | Yes |

| Contraceptive Patch (EE+progestin) | 6‑7 | ≥6weeks | ~0.01 | No (wait 6weeks) |

| Vaginal Ring (EE+progestin) | 15‑30 | ≥6weeks | ~0.02 | No (wait 6weeks) |

Practical Tips & Red Flags for Nursing Mothers Using EE

- Track infant weight weekly for the first month after starting any hormonal method.

- Watch for sudden changes in infant sleep patterns or excessive fussiness.

- If you notice a drop in milk output, try a short pump‑session before feeding to stimulate prolactin release.

- Consult your GP or a lactation consultant if you have any concerns about hormone exposure.

- Keep a medication log - note the brand, dose, and start date; this helps health professionals give precise advice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take a combined oral contraceptive while breastfeeding?

Yes, but most guidelines advise waiting until at least six weeks after delivery. After that point, the estrogen dose in a typical pill is low enough that infant exposure is negligible.

How much ethinylestradiol actually gets into my milk?

Studies show a milk‑to‑plasma ratio of 0.01‑0.03. For a 30µg pill, that translates to less than 1µg of EE per liter of milk - far below any level that would affect a newborn.

Will EE reduce my milk supply?

In most women, no. Only a small minority report a temporary dip in supply, usually when the pill is started before six weeks postpartum. The effect typically resolves on its own.

Are progesterone‑only methods safer for newborns?

Yes. Progesterone‑only pills, implants, and the copper IUD have no estrogen component, so virtually no hormone passes into breast milk. They are the preferred choice in the first six weeks.

What should I do if my baby seems unusually sleepy or irritable?

First, check feeding patterns and weight gain. If the concern persists, talk to your pediatrician and let them know you’re using a hormonal contraceptive. They may suggest a brief pause or switching to a progesterone‑only method.

lisa howard

October 17, 2025 AT 14:20When I first started nursing while on a combined oral contraceptive, the flood of advice from well‑meaning friends felt like a storm of conflicting voices, each insisting they knew the ultimate truth about ethinylestradiol and milk.

First, I was told the hormone was practically invisible in breast milk, a harmless whisper that would never sway my baby's growth.

Then, a different aunt swore that any estrogen could shut down prolactin and starve the little one, urging me to dump the pills immediately.

Meanwhile, the pediatrician quietly cited WHO data showing a milk‑to‑plasma ratio of only 0.01‑0.03, emphasizing the minuscule exposure.

I watched my infant’s weight chart climb steadily, defying the doom predictions that had haunted me.

Yet the anxiety persisted, bubbling over each feeding session as I wondered whether my milk was truly “safe.”

Over weeks, I scoured research articles, noting that most studies with over 200 lactating women found no statistical dip in milk volume or infant weight gain.

The pharmacokinetics of ethinylestradiol, with its lipophilicity and half‑life of roughly 24 hours, meant that only a nanogram‑scale amount ever entered the milk.

In practical terms, a 30 µg pill contributes less than a microgram per liter of milk, a dose dwarfed by natural estradiol fluctuations during lactation.

I also learned that estrogen can modulate prolactin, but the dosage in modern low‑dose pills is insufficient to cause clinically relevant suppression.

My own experience echoed these findings: my daily output stayed consistent, and my baby’s fussiness was no more than the usual newborn phase.

Nevertheless, the social pressure to switch to progesterone‑only methods or non‑hormonal contraception was relentless, as if any estrogen exposure were a crime against motherhood.

I decided to keep a balanced perspective, consulting a lactation specialist who confirmed that continuing a low‑dose COC after six weeks postpartum is generally considered safe by most health agencies.

In the end, I chose to stay on the pill, monitoring my infant’s growth and staying alert to any changes, but feeling empowered by the data rather than terrified by anecdote.

Ultimately, the takeaway is that the science supports the safety of ethinylestradiol in the early weeks for most mothers, and the emotional drama often stems more from misinformation than from pharmacology.

Cindy Thomas

October 21, 2025 AT 16:10Honestly, the whole panic about a single microgram of synthetic estrogen is overblown; the literature consistently shows no impact on infant weight gain, and the half‑life simply doesn’t allow for accumulation.

Most of the fear‑mongering comes from outdated textbooks that haven’t kept up with modern low‑dose formulations.

Don’t let anecdotal horror stories dictate your contraceptive choices – the data is crystal clear :)

Kate Marr

October 25, 2025 AT 18:00EE in milk is basically nothing 😊.

James Falcone

October 29, 2025 AT 18:50All this "safe after six weeks" nonsense is just globalist propaganda to push pills.

Frank Diaz

November 2, 2025 AT 20:40The epistemic framework surrounding ethinylestradiol exposure often collapses under the weight of reductionist thinking; by isolating a singular metabolite without contextualizing the endocrine milieu, one obscures the holistic nature of lactational physiology.

Thus, the critique lies not in the molecule itself but in the categorical imperative to deem any hormonal presence as inherently detrimental.

Mary Davies

November 6, 2025 AT 22:30I’m fascinated by how the body balances estrogen‑mediated prolactin suppression with the infant’s demand for nutrients, and yet the media loves to sensationalize the tiniest fraction of a drug making its way into milk.

It’s a drama that plays out in every parenting forum, where the odds of a minuscule dose causing real harm are dwarfed by the odds of a diaper exploding on a late‑night change.

Darryl Gates

November 11, 2025 AT 00:20Hey folks, just a quick heads‑up: if you’re tracking your baby’s growth and everything looks on‑track, there’s really no need to panic about the tiny EE levels.

Stay consistent with your check‑ups, and remember that a balanced diet and good hydration keep milk production solid.

Kevin Adams

November 15, 2025 AT 02:10Wow... this whole ethinylestradiol saga is like a soap opera-dramatic, over‑punctuated!!!

People throw around percentages like confetti, yet the actual exposure is microscopic-so why the endless exclamation???

Let’s calm the narrative and focus on the data, not the drama!!!

Katie Henry

November 19, 2025 AT 04:00Dear esteemed community, I wish to convey my sincere encouragement to all nursing mothers contemplating contraceptive options; rest assured that the scientific consensus affirms the safety of low‑dose ethinylestradiol beyond the initial postpartum fortnight, provided diligent monitoring is observed.

Joanna Mensch

November 23, 2025 AT 05:50It’s no coincidence that the agencies touting safety are funded by the very pharmaceutical conglomerates manufacturing these hormonal pills; the quiet whispers of a hidden agenda echo behind every "official" statement.

Consider the possibility that the minuscule milk‑to‑plasma ratio is deliberately downplayed to keep the market thriving, while covert research on long‑term neurodevelopmental impacts remains buried.

Even the subtle shift in language-from "no significant effect" to "generally safe"-might be a linguistic smokescreen designed to lull skeptical mothers into complacency.

One cannot ignore the pattern of data suppression that has plagued other drug safety narratives.

Nickolas Mark Ewald

November 27, 2025 AT 07:40Sounds good, I think it’s fine to keep using the pill if the doctor says so.

Chris Beck

December 1, 2025 AT 09:30These so‑called studies are a joke – they ignore the real harm to babies, and the government is in the pocket of pill makers.

Sara Werb

December 5, 2025 AT 11:20Look, I’m not saying the pills are evil, but have you ever noticed how every article pushes them like they’re the only option??!! It’s like they’re hiding something… The milk numbers are suspiciously low, almost like they’re fudged!! And don’t get me started on the “national” push for hormonal control…

Winston Bar

December 9, 2025 AT 13:10Honestly, I think the whole debate is overblown – it’s just a pill.